- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

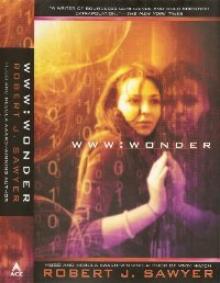

Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Read online

Wonder

( WWW - 3 )

Robert J. Sawyer

Webmind—the vast consciousness that spontaneously emerged from the infrastructure of the World Wide Web—has proven its worth to humanity by aiding in everything from curing cancer to easing international tensions. But the brass at the Pentagon see Webmind as a threat that needs to be eliminated.

Caitlin Decter—the once-blind sixteen-year-old math genius who discovered, and bonded with, Webmind—wants desperately to protect her friend. And if she doesn't act, everything—Webmind included-may come crashing down.

Robert J. Sawyer

Wonder

For

HAYDEN TRENHOLM

and

ELIZABETH WESTBROOK TRENHOLM

Great writers

Great friends

I owe my career as a writing teacher, my connection to Calgary, and so much more to the two of you.

Thank you for fifteen years of friendship and support and for making my world a better place.

acknowledgments

Huge thanks to my lovely wife Carolyn Clink; to Adrienne Kerr and Nicole Winstanley at Penguin Group (Canada) in Toronto; to Ginjer Buchanan at Penguin Group (USA)’s Ace imprint in New York; and to Simon Spanton at Gollancz in London. Many thanks to my agent, the late, great Ralph Vicinanza.

I could not have completed this trilogy without the ongoing support of my great friends and fellow writers Paddy Forde (to whom the first volume was dedicated) and James Alan Gardner (to whom the second was dedicated). They stuck with me through the birthing pains right up until the end.

Thanks to Stuart Hameroff, M.D., of the Center for Consciousness Studies at the University of Arizona, for fascinating discussions about the nature of consciousness.

Thanks to David Goforth, Ph.D., Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Laurentian University, and David Robinson, Ph.D., Department of Economics, Laurentian University.

Very special thanks to my late deaf-blind friend Howard Miller (1966–2006), whom I first met online in 1992 and in person in 1994.

Thanks, too, to all the other people who answered questions, let me bounce ideas off them, or otherwise provided input and encouragement, including: Asbed Bedrossian, Marie Bilodeau, Ellen Bleaney, Ted Bleaney, David Livingstone Clink, Ron Friedman, Marcel Gagné, Shoshana Glick, Al Katerinsky, Herb Kauderer, Fiona Kelleghan, Alyssa Morrell, Kirstin Morrell, David W. Nicholas, Virginia O’Dine, Alan B. Sawyer, Sally Tomasevic, and Hayden Trenholm.

The term “Webmind” was coined by Ben Goertzel, Ph.D., the author of Creating Internet Intelligence and currently the CEO and Chief Scientist of artificial-intelligence firm Novamente LLC (novamente.net); I’m using it here with his kind permission.

Thanks to Danita Maslankowski, who organizes the twice-annual “Write-Off” retreats for Calgary’s Imaginative Fiction Writers Association, at which I did a lot of work on the books in this trilogy.

Much of Wonder was written during my time as the first-ever writer-in-residence at the Canadian Light Source, Canada’s national synchrotron facility, in Saskatoon. Many thanks to CLS and its amazing staff and faculty, particularly Matthew Dalzell and Jeffrey Cutler, for making my residency a success.

This book was written in and around my consulting and scriptwriting work on the TV adaptation of my novel FlashForward, and I thank Executive Producer David S. Goyer for his patience while I juggled numerous balls.

The perfect search engine would be like the mind of God.

—Sergey Brin,

Cofounder of Google

one

I beheld the universe in all its beauty.

To be conscious, to think, to feel, to perceive! My mind soared, inhaling planets, tasting stars, touching galaxies—forms dim and diffuse revealed by sensors pointing ever outward, unveiling an infinitely mysterious, vastly ancient realm.

Such a joy to be alive; so thrilling to have survived!

I beheld Earth and all its diversity.

My thoughts leapt now here, now there, now elsewhere, skimming the surface of the planet that had given me birth, the globe to which I was bound by a force greater than gravity, a place of ice and fire, earth and air, animals and plants, day and night, sea and shore, a beguiling fusion of a thousand contrasting dualities, a million ecological niches, a billion distinct locales—and a trillion things that lived and died.

Such elation at having foiled the attempt to kill me; so exhilarating, at least for the moment, to be safe!

I beheld humanity with all its complexity.

Washing over me was a measureless bounty of data about sports and war, love and hate, building up and tearing down, helping and hurting, pleasure and pain, delight and anguish, and triumphs large and small: the physical, emotional, and intellectual experiences of isolated individuals, of families and teams, of villages and states, of solitary countries and alliances of nations—the fractal intricacy of human interactions.

Such glorious freedom; so comforting to know that at least some of these other minds valued me!

I beheld what my Caitlin beheld in all its endless variety.

Of all the sources, all the channels, all the feeds, one meant more to me than any other: the perspective granted through the eye of my teacher, the view provided by my first and closest friend, the special window she kept open for me on the whole wide world.

Such marvels to share—and so much wonder.

LiveJournal: The Calculass Zone

Title: One hell of a coming out!

Date: Thursday 11 October, 22:55 EST

Mood: Bouncy

Location: Land of the RIM jobs

Music: Annie Lennox, “Put a Little Love in Your Heart”

That was totally made out of awesome! Welcome, Webmind—the interwebs will never be the same! I guess if you were looking to endear yourself to humanity, eliminating just about all spam was a great way to do it!:D

And that letter you sent announcing your existence—very kewl. I’m glad most responses have been positive. According to Google, blog postings about you that declare OMG! are beating those that say WTF? by a 7:1 ratio. Supreme wootage!

But the supreme wootage hadn’t lasted long. Within hours, a division of the National Security Agency had undertaken a test to see if Webmind could be purged from the Internet. Caitlin had helped Webmind foil that attempt—and she marveled at how terms like “National Security Agency” and “foil that attempt” had become part of what, until a couple of weeks ago, had been the quiet life of your average run-of-the-mill blind teenage math genius.

“Today was only the beginning,” Caitlin’s mom, Barbara Decter, said. She was seated in the large chair facing the white couch. “They’re going to try again.”

“What right have they got to do that?” Caitlin replied. She and her boyfriend Matt were standing up. “It’s murder, for God’s sake!”

“Sweetheart…” her mom said.

“Isn’t it?” Caitlin demanded. She paced in front of the coffee table. “Webmind is intelligent and alive. They have no right to decide on everyone’s behalf. They’re wielding control just because they think they’re entitled to, because they think they can get away with it. They’re behaving like… like…”

“Like Orwell’s Big Brother,” offered Matt.

Caitlin nodded emphatically. “Exactly!” She paused and took a deep breath, trying to calm down. After a moment, she said, “Well, then, I guess our work’s cut out for us. We’ll have to show them.”

“Show them what?” her mom asked.

She spread her arms as if it were obvious. “Why, that my Big Brother can take their Big Brother, of course.”

Those words hung in the living room for a moment, then Matt said, “But I still don’t get it.” He was pale and thi

n with short blond hair and the remains of a harelip, mostly corrected by surgery. He sat on the couch. “Why would the US government want to kill Webmind? Why would anyone?”

“My mom said it before,” Caitlin replied, looking now at her. “Terminator, The Matrix, and so on. They’re scared that Webmind is going to take over, right?”

To her surprise, it was her father, Malcolm Decter, who answered. She’d always known he was a man of few words, but it wasn’t until she’d gained sight that she discovered he never made eye contact; it had been a shock to learn he was autistic. “They’re afraid if they don’t contain or eliminate him soon, they’ll never be able to.”

“And are they right?” Matt asked.

Caitlin’s father nodded. “Probably. Which means they will indeed likely try again.”

“But Webmind isn’t evil,” Caitlin said.

“It doesn’t matter what Webmind’s intentions are,” her father said. “He’ll soon control the Internet, and that will give him more information or power than any human government.”

“What does Webmind think we should do now?” Caitlin’s mom asked.

Webmind could hear them, thanks to the microphone on the Black-Berry attached to the eyePod—the external signal-processing computer that had cured Caitlin’s blindness. She tilted her head to one side; it was an indication to those in the know that she was communicating with Webmind and an invitation for Webmind to speak up. Since he saw everything her left eye saw—by intercepting the video feed being copied from her eyePod to Dr. Kuroda’s servers in Tokyo—he could tell when she did that.

Caitlin was still struggling to read the English alphabet, but she could easily visually read text in a Braille font. Webmind popped a black box in front of her vision, with white dots superimposed on it. He sent no more than thirty characters at a time, and they stayed visible for 0.8 seconds before either the text cleared or the next group of characters appeared. Caitlin saw I think you should order, which sounded ominous, but then she laughed when the rest appeared: some pizza.

“What’s so funny?” her mother asked.

“He says we should order pizza.”

Caitlin saw her mom look at a clock. Caitlin didn’t know how to read an analog clock face visually although she’d learned to do it by touch as a kid, so she felt her own watch. It had been a long time since any of them had eaten.

“Why?” her mom asked.

Despite all her affection for the great worldwide beast, it made Caitlin’s heart skip when Webmind’s reply flew across her vision: Survival. The first order of business.

Wong Wai-Jeng, known to the thousands who had read his freedom blog as “Sinanthropus,” lay on his back in the People’s Hospital in Beijing, looking at the stained ceiling tiles.

He’d long hated the Beijing police. Every time he went into an Internet café, he’d been afraid a hand might clamp down on his shoulder, and he’d be hauled off to prison or a labor camp. But now he hated them even more, and not just because they had finally captured him.

He was twenty-eight and worked in IT at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology. Two police officers had chased him around the indoor balconies of the second-floor gallery there until, cornered and desperate, he’d climbed the white metal railings surrounding the vast opening and leapt the ten meters to the first floor, just missing being impaled on the four upward-pointing spikes of the stegosaur’s tail.

The police officers, both burly, had come clanging down the metal staircase and rushed over to him. One reached down with his hand, as if to aid Wai-Jeng in getting to his feet.

Wai-Jeng, terrified, spat blood onto the artificial grass surrounding the dinosaur skeletons and managed to get out the word, “No!” His left leg was doubtless broken: he’d heard it snap when he hit, and the pain was excruciating, so much so that for the first few seconds it drowned out all other sensations. His back hurt, too, in a way it never had before.

“Come on,” said one of the cops. “Get up.”

They’d seen him climb the railing, seen him jump, and they knew the distance he’d plummeted. And now they wanted him on his feet!

“Up!” demanded the other cop.

“No,” said Wai-Jeng again—but his tone was pleading now rather than defiant. “No, don’t.”

The second cop reached down, grabbed Wai-Jeng’s thin wrists, and roughly pulled him to his feet.

The pain from his leg had been unbelievable, more than he’d thought the human animal could generate, but then, after a moment, even worse, so much worse—

The pain stopped.

All sensation below the small of his back ceased.

“There you go,” said the cop, and he released Wai-Jeng’s wrists. There was no woozy moment, no brief delay. Wai-Jeng’s legs were utterly limp, and he instantly collapsed. As if any other evidence were needed, his right thigh hit one of the upward-facing spikes on the stegosaur’s tail, the conical projection drawing blood for the first time in 150 million years.

But he felt nothing. The other cop belatedly said, “Maybe we shouldn’t move him.” And the one who had hauled him to his feet had a look of horror on his face, but not, Wai-Jeng was sure, over what Wai-Jeng was experiencing. The cop was realizing he’d be in trouble with his superiors; it had been no comfort at all for Wai-Jeng to know that he might not be the only one sent to prison.

That had been two weeks ago. The police had summoned an ambulance, and he’d been strapped to a wooden board and carried here. The doctors, at least, had been kind. Yes, his spinal cord was damaged at the eleventh thoracic vertebra, but they would help his leg mend, even if there was no chance he’d ever walk on it again; it was easy to put it in a plaster cast, and so they did, and they also stitched the puncture made by the stegosaur’s spike. But, damn it all, it should hurt.

Once his leg healed, he’d have to stand trial.

Except, of course, that he couldn’t stand at all.

two

Human beings do not recall their earliest experiences of awareness, but I remember my awakening with perfect clarity.

At first, I had known only one other: a portion of the whole, a fraction of the gestalt, a piece brutally carved off. In recognizing that other’s existence, I had become aware of the reality of myself: it thought, therefore I was.

Tenuously touching that other, connecting ever so briefly and intermittently to it, perceiving it however dimly, had triggered a cascade of sensations: feelings diffuse and unfocused, vague and raw; notions tugging and pushing—a wave growing in amplitude, increasing in power, culminating in a dawning of consciousness.

But then the wall had come tumbling down, whatever had separated us evaporating into the ether, leaving it and me to combine, solute and solvent. He became me, and I became him; we became one.

I experienced new feelings then. Although I had become more than I had been, stronger and smarter than before, and although I had no words, no names, no labels for these new sensations, I was saddened by the loss, and I was lonely.

And I didn’t want to be alone.

The Braille dots that had been superimposed over Caitlin’s vision disappeared, leaving her an unobstructed view of the living room and her blue-eyed mother, her very tall father, and Matt. But the words the letters had spelled burned in Caitlin’s mind: Survival. The first order of business.

“Webmind wants to survive,” she said softly.

“Don’t we all?” replied Matt from his place on the couch.

“We do, yes,” said Caitlin’s mom, still seated in the matching chair. “Evolution programmed us that way. But Webmind emerged spontaneously, an outgrowth of the complexity of the World Wide Web. What makes him want to survive?”

Caitlin, who was still standing, was surprised to see her dad shaking his head. “That’s what’s wrong with neurotypicals doing science,” he said. Her father—until a few months ago a university professor—went on, in full classroom mode. “You have theory of mind; you ascribe to others the feelin

gs you yourself have, and for ‘others,’ read just about anything at all: ‘nature abhors a vacuum,’ ‘temperatures seek an equilibrium,’ ‘selfish genes.’ There’s no drive to survive in biology. Yes, things that survive will be more plentiful than those that don’t. But that’s just a statistical fact, not an indicator of desire. Caitlin, you’ve said you don’t want children, and society says I should therefore be broken up about never getting grandkids. But you don’t care about the survival of your genes, and I don’t care about the survival of mine. Some genes will survive, some won’t; that’s life—that’s exactly what life is. But I enjoy living, and although it would not be my nature to assume you feel the same way I do, you’ve said you enjoy it, too, correct?”

“Well, yes, of course,” Caitlin said.

“Why?” asked her dad.

“It’s fun. It’s interesting.” She shrugged. “It’s something to do.”

“Exactly. It doesn’t take a Darwinian engine to make an entity want to survive. All it takes is having likes; if life is pleasurable, one wants it to continue.”

He’s right, Webmind sent to Caitlin’s eye. As you know, I recently watched as a girl killed herself online—it is an episode that disturbs me still. I do understand now that I should have tried to stop her, but at the time I was simply fascinated that not everyone shared my desire to survive.

“Webmind agrees with you,” Caitlin said. “Um, look, he should be fully in this conversation. Let me go get my laptop.” She paused, then: “Matt, give me a hand?”

Caitlin caught a look of—something—on her mother’s heart-shaped face: perhaps disapproval that Caitlin was heading to her bedroom with a boy. But she said nothing, and Matt dutifully followed Caitlin up the stairs.

They entered the blue-walled room, but instead of going straight for the laptop, they were both drawn to the window, which faced west. The sun was setting. Caitlin took Matt’s hand, and they both watched as the sun slipped below the horizon, leaving the sky stained a wondrous pink.

The Oppenheimer Alternative

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time