- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Page 11

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Read online

Page 11

(Run commercials: Archer Daniels Midland’s new all-vegetable automobile. General Dynamics—“our work may be classified, but we’re a good corporate citizen.” Merrill Lynch—“because someday the economy will turn around.”)

(Roll pre-recorded backgrounder.)

(Fade up in studio.)

Stephanopoulis: “Kyle, thank you.”

(Recap guests and panelists.)

(Insert Peter Hobson on wall monitor, with dateline display at top showing “Toronto.”)

Sam Donaldson, leaning forward: “Professor Hobson, your discovery of the soulwave could be seen as a great liberator of oppressed people, final proof that all men and women are created equal. What effect do you think your discovery will have on totalitarian regimes?”

Hobson, politely: “Excuse me, but I’m not a professor.”

Donaldson: “I stand corrected. But don’t duck my question, sir! What effect will your discoveries have on the human-rights violations going on in the eastern Ukraine?”

Hobson, after a moment’s reflection: “Well, I’d love to think that I’ve struck a blow for human equality, of course. But it seems that our ability to be inhuman has survived every challenge to it in the past.”

George Will, over steepled fingers: “Dr. Hobson, the average American, struggling under the burden of an excessive government with a ravenous appetite for tax dollars, cares not one whit about the geopolitical ramifications of your research. The average church-going American wants to know, in precise and plain language, sir, exactly what characteristics the afterlife actually has.”

Hobson, blinking: “Is that a question?”

Will: “It is the question, Dr. Hobson.”

Hobson, shaking head slowly: “I have no idea.”

CHAPTER 16

Peter was not about to let his new-found celebrity interfere with his Tuesday evening dinners with Sarkar at Sonny Gotlieb’s. But he did have something very specific that he wanted to explore with Sarkar, and he began without preamble. “How do you create an artificial intelligence? You work in that field—how do you do it?”

Sarkar looked surprised. “Well, there are many ways. The oldest is the interview method. If we wanted a system to do financial planning, we would ask questions of several financial planners. Then we reduce the answers to a series of rules that can be expressed in computer code—‘if A and B are true, do C.’”

“But what about that scanner my company built for you? Aren’t you doing full brain dumps of specific people now?”

“We’re making good progress toward that. We’ve got a prototype called RICKGREEN, but we’re not ready to go public with it. You know that comedian, Rick Green?”

“Sure.”

“We did a full scan of him. The resulting system can now tell jokes that are just as funny as the ones the real Rick tells. And by giving it access to the Canadian Press and UPI news feeds, it can even generate new topical humor.”

“Okay, so you can essentially clone in silicon a specific human mind—”

“Get with the twenty-first century, Peter. We use gallium arsenide, not silicon.”

“Whatever.”

“But you have hit upon what makes the problem crisp: we are just at the point where we can clone one specific human mind—a shame that such a technique did not exist in time to scan Stephen Hawking. But there are very few applications in which you want the knowledge of just one person. For most expert systems, you really want the combined knowledge of many practitioners. So far, there is no way to combine, say, Rick Green and Jerry Seinfeld, or to build a combined Stephen Hawking / Mordecai Almi neural net. Although I had high hopes for this technology, I suspect most of the contracts we’ll get will be for duplicating the brains of autocratic company presidents who think their heirs are going to be interested in what they have to say after they’re dead.”

Peter nodded.

“Besides,” said Sarkar, “total brain dumps are turning out to be a tremendous waste of resources. When we created RICKGREEN, all we were really interested in was his sense of humor. But the system also gives us everything else Rick knows, including his approaches to raising his children, an endless amount of expertise about model trains, which are his hobby, and even his cooking technique, something no one in his right mind would want to emulate.”

“Can’t you pare it down to isolate just the sense of humor?”

“That’s difficult. We’re getting good at decoding what each neural net does, but there are many interconnections. When we tried deleting the part about child-rearing, we found the system no longer made jokes about family life.”

“But you can make an accurate duplicate of a specific human mind on a computer?”

“It’s a brand-new technique, Peter. But, so far, yes, the duplication seems accurate.”

“And you can, at least to some extent, decode the functions of the various neural interconnections?”

“Yes,” said Sarkar. “Again, we’ve only tried it on the RICKGREEN prototype—and that was a limited model.”

“And, once you’ve identified a function, you can delete it from the overall brain simulacrum?”

“Bearing in mind that deleting one thing may change the way something that seems unrelated will respond, yes, I’d say we’re at the point at which we can do that.”

“All right,” said Peter. “Let me propose an experiment. Say we make two copies of a specific person’s mind. In one of them you excise everything related to the physical body: hormonal responses, sexual urges, things like that. And in the second one, you remove everything related to bodily degeneration, to fear of old age and dying, and so on.”

Sarkar ate a matzo ball. “And what would the point be?”

“The first one would be to answer that question everyone keeps asking me: what is life after death really like? What parts of the human psyche could persist separate from the body? And, while we’re at it, I figure we’d do the second one—a simulation of a being who knew he was physically immortal, like someone who has undergone that Life Unlimited process.”

Sarkar stopped chewing. His mouth hung open, giving an undignified view of a masticated dumpling. “That’s—that’s incredible,” he said at last, around his food. “Subhanallah, what an idea.”

“Could you do it?”

Sarkar swallowed. “Maybe,” he said. “Electronic eschatology. What a concept.”

“You’d need to make the two brain dumps.”

“We’d do the dump once, of course. Then we’d just copy it twice.”

“Copy it once, you mean.”

“No, twice,” said Sarkar. “You can’t do an experiment without a control; you know that.”

“Right,” said Peter, slightly embarrassed. “Anyway, we’d make one copy which we would modify to simulate life after death. Call it—call it the Spirit simulacrum. And another to simulate immortality.”

“And the third we would leave unmodified,” said Sarkar. “A baseline or control version that we can compare to the original living person to make sure that the simulacra retain their accuracy as time goes on.”

“Perfect,” said Peter.

“But you know, Peter, this wouldn’t necessarily simulate true life-after-death. It’s life outside the physical body—but who knows if the soulwave carries with it any of our memories? Of course, if it doesn’t, then it’s not really a meaningful continuation of existence. Without our memories, our pasts, what we were, it wouldn’t be anything we’d recognize as a continuation of the same person.”

“I know,” said Peter. “But if the soul is anything like what people believe it to be like—just the mind, without the body—then this simulation, at least, would give us some idea of what that kind of soul would be like. Then I could have something intelligent to say the next time I get asked that ‘What’s life after death really like?’ question.”

Sarkar nodded. “But why the research into immortality?”

“I went to one of those Life Unlimited seminars a while ago

.”

“Really? Peter, surely you don’t want that.”

“I—I don’t know. It’s fascinating, in a way.”

“It’s stupid.”

“Maybe—but it seems we could kill two birds with one stone with this research.”

“Perhaps,” said Sarkar. “But who would we simulate?”

“How about you?” asked Peter.

Sarkar raised a hand. “No, not me. The last thing I want to do is live forever. True joy is possible only after death; I look forward to the felicity to be given to my realized soul in the next world. No, they were your questions, Peter. Why not use you?”

Peter stroked his chin. “All right. If you’re willing to undertake the project, I’m willing both to fund it and to be the guinea pig.” He paused. “This could answer some really big questions, Sarkar. After all, we know now that both physical immortality is possible and that some form of life after death exists. It would be a shame to choose one if the other turned out to be better.”

“Hobson’s choice,” said Sarkar.

“Eh?”

“Surely you know the phrase. Your last name is Hobson, after all.”

“I’ve heard the expression once or twice.”

“It refers to Thomas Hobson, a liveryman in England in, oh, the seventeenth century, I think. He rented out horses, but required his customers to take either the horse nearest the stable door or none at all. A ‘Hobson’s choice’ is a choice that offers no real alternative.”

“So?”

“So you don’t get an alternative. Do you seriously think that if you were to bankrupt yourself buying nanotechnology immortality that Allah couldn’t take you anyway if He wanted to? You have a destiny, as do I. We have no choice. When it’s time for you to go to the stable, the horse nearest the door will be the one that is meant for you. Call it Hobson’s choice or qadar Allah or kismet—whatever term you use, it’s the foredestiny of God.”

Peter shook his head. He and Sarkar rarely talked about religion, and he was beginning to remember why. “Are you willing to undertake the project?”

“Sure. My part is easy. You’re the one who is going to have to face himself. You will see your own personality, the inner workings of your own mind, the interconnections that drive your thoughts. Do you really choose to do that?”

Peter reflected for a moment. “Yes,” he said. “I really do choose that.”

Sarkar smiled. “Hobson’s choice,” he said, and signaled the server to bring the check.

NET NEWS DIGEST

The Archdiocese of Houston, Texas, would like to remind everyone that this coming Wednesday, November 2, is All Souls’ Day—the day on which prayers are offered for souls in purgatory. Because of the recent surge of interest in this topic, a special mass will be held at the Astrodome Wednesday evening at 8:00 p.m.

The front-page editorial in the November issue of Our Bodies, newsletter of the group Women in Control, headquartered in Manchester, England, denounces the discovery of so-called fetal soulwaves as “yet another attempt by men to impose control over women’s bodies.”

Raymond Moody’s Life After Life, first published in 1975, was reissued this week by NetBooks and immediately surged to number two on The New York Times daily bestsellers list in the category of premium-download non-fiction.

In spirited trading, Hobson Monitoring Limited (TSX:HML) closed today at 57-1/8, up 6-3/8 from the day before, on a volume of 35,100 shares. This represents a new 52-week high for the Toronto-based biomedical equipment maker.

A demonstration was held today out front of the free-standing Morgentaler Abortion Clinic in Toronto, Ontario, by the organization Defenders of the Unborn. “Abortion prior to the arrival of the soulwave is still a sin in the eyes of God,” said protester Anthoula Sotirios. “For the first nine weeks of pregnancy, the fetus is a temple, being prepared for the arrival of the divine spark.”

CHAPTER 17

Thursday evening at home. Peter had long ago programmed the household computer to scan the TV listings for topics or shows that would interest him. For two years, he’d had a standing order for the PVR to record the film The Night Stalker— a made-for-TV movie he’d first encountered as a teenager—but so far it hadn’t come on. He also asked to be alerted whenever an Orson Welles film was on, whenever Ralph Nader or Steven Pinker was going to be on any talk show, and for any episodes of Night Court in which Brent Spiner guest-starred.

Tonight, DBS Cairo was showing Welles in The Stranger in English with Arabic subtitles. Peter’s PVR had a subtitle eraser—it scanned the parts of the image adjacent to the subtitles, as well as the frames before and after the subtitles appeared, and filled in an extrapolation of the picture that had been obscured by the text. Quite a find: Peter hadn’t seen The Stranger for twenty years. His PVR hummed quietly, recording it.

Maybe he’d watch it tomorrow. Or Saturday.

Maybe.

Cathy, sitting across the room from him, cleared her throat, then said, “My coworkers have been asking about you. About us.”

Peter felt his shoulders tense. “Oh?”

“You know: about why we haven’t been at the Friday-night gatherings.”

“What have you told them?”

“Nothing. I’ve made excuses.”

“Do they—do you think they know about … about what happened?”

She considered. “I don’t know. I’d like to think they don’t, but …”

“But that asshole Hans has a mouth on him.”

She said nothing.

“Have you heard anything? Snide comments? Innuendoes? Anything to make you think your coworkers know?”

“No,” said Cathy. “Nothing.”

“Are you sure?”

She sighed. “Believe me, I’ve been particularly sensitive to what they’ve been saying. If they are gossiping behind my back, I haven’t picked up on it. No one has said a word to me. Really, I suspect they don’t know.”

Peter shook his head. “I—I don’t think I could take it if they knew. Facing them, I mean. It’s …” He paused, trying to come up with the appropriate word. “… humiliating.”

She knew better than to reply.

“Damn,” said Peter. “I hate this. I really fucking hate this.”

Cathy nodded.

“Still,” said Peter, “I suppose ...I suppose if we’re ever going to have a normal life again, we’ve got to start going out, seeing people.”

“Danita thinks that would be wise, too.”

“Danita?”

“My counselor.”

“Oh.”

She was quiet for a moment, then: “Hans left town today. He’s attending a conference. If we went out after work with my friends tomorrow, he wouldn’t be there.”

Peter took a deep breath, exhaled it noisily. “You’re sure he won’t be there?” he said.

She nodded.

Peter was silent for a time, marshaling his thoughts. “All right,” he said at last. “I’ll give it a try, as long as we don’t stay too long.” He looked her in the eyes. “But you better be right about him not being there.” His voice took on a tone Cathy had never heard before, a stone-cold bitterness. “If I see him again, I’ll kill him.”

PETER ARRIVED at The Bent Bishop early so that he could be sure of the seat directly beside his wife. The crew from Doowap Advertising had found a long table in the middle of the room this time, so they were all in captain’s chairs. Peter did indeed get to sit next to Cathy. Opposite him was the pseudointellectual. His bookreader was loaded with Camus.

“’Evening, Doc,” said Pseudo. “You’re certainly in the news a lot these days.”

Peter nodded. “Hello.”

“Not used to seeing you here so early,” Pseudo said.

Peter immediately realized his mistake. Everything should have been exactly as before. He should be doing nothing that would attract attention to him or Cathy.

“Ducking reporters,” Peter said.

Pseudo nodde

d, and lifted a glass of dark ale to his lips. “You’ll be glad to know Hans won’t be here.”

Peter felt his cheeks flush, but in the dim lighting of the pub it was probably invisible. “What do you mean?” Peter had intended the question to come out neutrally, but there’d been an undeniable edge to it. Next to him, Cathy patted his knee under the table.

Pseudo lifted his eyebrows. “Nothing, Doc. It’s just that he and you don’t seem to always get along. He was ribbing you a fair bit last time.”

“Oh.” The server had appeared. “Orange juice,” said Peter.

The server turned to Cathy, her face a question. “Mineral water,” Cathy said. “With lime.”

“Nothing to drink today?” said Pseudo, as if the very concept was an affront to all things decent.

“I’ve, ah, got a headache,” said Cathy. “Took some aspirin.”

There was no end to lies, thought Peter. She couldn’t say, I’ve stopped drinking because last time I got drunk I let a coworker fuck me. Peter felt his fists clenching beneath the table.

Two more of Cathy’s friends arrived, a man and a woman, both middle aged, both slightly heavy. Cathy said hi to them. “Light turnout tonight,” said the man. “Where’s Hans?”

“Hans is in Beantown,” said Pseudo. Peter thought he’d been waiting all day to get to say “Beantown.” “At that interactive-video conference.”

“Gee,” said the woman. “It won’t be the same without Hans.”

Hans, thought Peter. Hans. Hans. Each uttering of his name was like a knife thrust. Haven’t these people ever heard of pronouns?

The server reappeared and put some reconstituted orange juice in front of Cathy, and a small bottle of Perrier and a glass with a bruised lime wedge pushed into its rim in front of Peter. All non-alcoholic drinks were the same to her, he guessed. Peter and Cathy exchanged drinks, and the server took the newcomers’ orders.

“So how are things with the two of you?” asked the newly arrived man, waving a hand generally at Peter and Cathy.

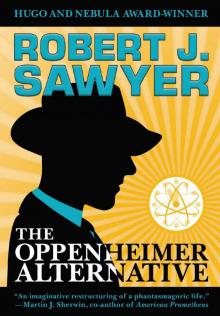

The Oppenheimer Alternative

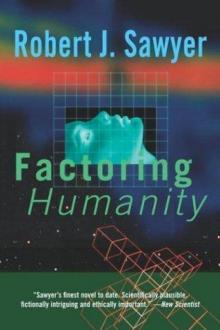

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

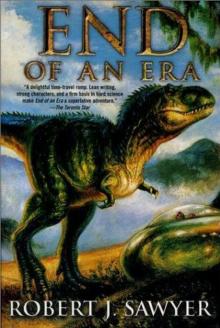

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time