- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

Foreigner qa-3 Page 12

Foreigner qa-3 Read online

Page 12

"Incredible," said Karshirl. She turned and bowed to Novato. "I agree: this is a fascinating thing for an engineer to study. Thank you for requesting me — although I’ll admit I’m surprised you asked for me. I’m young, after all; there are much older and more experienced engineers who would enjoy a chance to examine this."

"You’re not that young, Karshirl," said Novato. "You’re eighteen or so; I was just eleven, an apprentice glassworker, when I invented the far-seer."

"Still…" said Karshirl, then, evidently deciding not to press her good fortune, "Thank you very much. I do appreciate the opportunity." The younger female leaned back on her tail and looked up at the tower, lost in the fog. "How tall is the tower?" she asked

"I have no idea," said Novato.

Karshirl clicked her teeth. "Good Novato, have you forgotten your trigonometry? All you have to do is move a known distance from the tower’s base — a hundred paces, say — then note the angle between the ground and the top of the tower. Any good set of math tables will give you the height."

"Of course," said Novato. "But that’s predicated on the assumption that one can see the top of the tower. But we can’t, even on the clearest of days. The tower simply goes up and up, straight to the zenith. I’ve seen it pierce right through clouds, with the cloud looking like a gobbet of meat skewered on a fingerclaw. The tower is sufficiently narrow that it fades from view before its summit is reached. The best time to view it is on clear mornings just before dawn, when the tower itself is already illuminated by the sun, but the sky is still dark. Still, I can’t make out its apex. I’ve looked at its upper reaches with a far-seer, and, again, it fades from view rather than coming to a discrete end."

"That’s incredible," said Karshirl.

"Indeed."

"But wait — there’s another way to measure it. You’ve said there is a vehicle of some kind moving up its interior?"

"Several, as it turns out. We call them lifeboats."

"Well, all you have to do is mark one of the lifeboats, so you can be sure to recognize the same one later. Measure the distance between two of the tower’s rungs — you can do that, at least, with trig, even if you can’t actually reach the rungs. Choose a couple of rungs that are a good distance apart and also are a good ways up the shaft so that the lifeboat will be up to speed by the time it passes them. Then simply see how long it takes for a lifeboat to traverse that distance. That will give you its traveling speed. After that, all you have to do is wait for the lifeboat to make a round trip up and down the shaft. Assuming the lifeboats do indeed go all the way to the top, and assuming they travel at a constant speed, you’ll be able to calculate the tower’s height by dividing half the total elapsed time by the lifeboat’s known speed."

If Karshirl had been looking at Novato, instead of tipping her muzzle up at the tower, she’d have stopped before getting to the end of her explanation, since Novato’s face made it clear that she’d already thought of all this. "We tried that, of course," said Novato. "The lifeboats accelerate quickly at first, but almost immediately seem to reach their maximum velocity. It seems the lifeboats are moving at something like one hundred and thirty kilopaces per day-tenth."

"Good God!" said Karshirl, her eyelids strobing up and down. "That’s faster than even a runningbeast can manage."

"Twice as fast, to be precise," said Novato. "And it takes the lifeboats — wait for this — twenty days to make the round trip. Now, granted, there’s a lot of room for error — these are just back-of-a-sash calculations — but if you do the math, that would imply that the tower is on the order of thirteen thousand kilopaces tall."

"But, good Novato, our entire world has a diameter of only twelve thousand kilopaces," said Karshirl. "You can’t be seriously suggesting that the tower is taller than our world is wide. Something must be going on that we can’t see. The lifeboats must stop at the top for days on end, or else slow down once they get out of sight."

Novato felt slightly surprised. She’d selected Karshirl for her own reasons, but was beginning to regret the choice. "Surely you wouldn’t discard data just because it doesn’t fit your expectations."

"Oh, indeed," said Karshirl, somewhat piqued. "I’m a good little scientist, too. However, I am also a structural engineer, which is something you are not. And I tell you, Novato, based on well-established engineering principles, that the tower cannot be as tall as you say. Look: stability is a real concern when building towers. You know the old story of the Tower of Howlee, told in the — the fiftieth, I think — sacred scroll? That was a tower that would reach up to the sky so that one could touch the other moons." Novato nodded.

"But Howlee’s Tower is utterly impossible," said Karshirl. "A sufficiently long, narrow object will buckle if it is held straight up." She raised a hand. "Now, I know you’ve said that this tower is made out of stuff that’s harder than diamond. That’s irrelevant. No matter how great its compressive strength, such a tower will buckle if the ratio of its length to width goes above a certain value. In the old scroll, which was written long before we knew just how far away the other moons were, Howlee’s Tower was said to be twenty-five kilopaces tall, and had a base fifty paces on a side. You couldn’t build a tower like that out of any material. In fact, one can’t even build a scale replica of Howlee’s Tower, at any scale. It will buckle and collapse."

"Because of the buffeting of the wind?" asked Novato.

"No, it’s not that. You can’t even build a scale model of Howlee’s Tower inside a sealed glass vessel, in which there are no air currents at all."

"Why not?" said Novato.

Karshirl looked around vaguely, as if wishing she had something to draw a picture on. Failing to find anything, she simply turned back and faced Novato. "Let’s say you build a tower that’s a hundred paces tall and has a base of, oh, one square centipace."

Novato’s tail swished in acceptance. "All right."

"Well, visualize the top of this structure: it’s a flat roof, one square centipace in area."

"Yes."

"Consider the corners of that roof. There’s no way they will be perfectly even. One of them is bound to be a small fraction lower than the others. Even if they are all even originally, as the ground shifts even infinitesimally under the tower’s weight, one corner will end up lower than the others."

"Ah, I see: the tower, of course, will lean toward the lowest corner, even if only very slightly."

"Right. And when the tower does lean, that makes the lowest corner even lower, and the tower will lean some more, and on and on until the whole thing is leaning over like a tree in a storm — no matter how strong the building material is."

"So the tower can’t be thirteen thousand kilopaces high," said Novato.

"That’s right. Indeed, it can’t be anywhere near that high."

Novato leaned back on her tail. "Obviously the pyramidal base gives the tower some stability, but the actual tower itself is only fourteen paces wide. How high could a tower that wide be?"

"Oh, I’m no Afsan," said Karshirl. "I’d need to sit down with ink and writing leather to figure that out."

"Roughly, though. How high? Remember, this tower extends well above the clouds."

"And how high up are the clouds?" asked Karshirl.

"Oh, it varies. Say ten kilopaces. Could a tower fourteen paces wide be even that tall without collapsing in the manner you’ve described?"

Karshirl was silent for a time. "Ah, well, um, probably not," she said at last.

Novato nodded. "So some other factor is at work here." She gestured at the vast blue pyramid and the narrow four-sided tower thrusting up from its apex toward the vault of heaven. "Somehow, impossible as it seems, this tower does stand."

*13*

No one normally sat in the Dasheter’s lookout bucket when the ship was at rest. Still, even when just walking the decks, old Mar-Biltog couldn’t keep himself from occasionally scanning the horizon, so it was no surprise that he was the first to catch sight of them.

He thumped the deck with his tail. The fools! Toroca said he’d warned them! Cupping his muzzle with his hands, Biltog shouted, "Boats approaching!"

Toroca, who happened to be passing fairly near, ran as fast as he could with his healing leg to the railing around the Dasheter’s edge. Biltog had already made his way across the little bridge that joined the Dasheter’s forehull to its aft, and Toroca could hear his now-distant voice shouting again, "Boats approaching!"

And so they were: two long, orange boats. Typical Other designs. The lead boat contained five Others, each operating a pair of oars. They were packed in more tightly than Quintaglios could ever manage. The rear boat was too far away for Toroca to count its occupants, but it was likely a similar number.

In response to Biltog’s calls, Quintaglios were coming up the ramps onto the top deck. That was the worst thing that could happen. "No!" shouted Toroca. "Go below! Stay below!"

Babnol was emerging about ten paces away. Toroca pointed at her. "Get everyone below!" "What’s happening?" she said. "Get everyone below now! Others are coming!" Babnol reacted immediately, turning tail and heading back down the ramp. Toroca heard her entreating sailors to go to their cabins.

Toroca hurried toward the ropes that led up to the lookout’s bucket. He began to climb. When he got four body-lengths up, where he was sure the Others could see him, he waved his arm widely. "Go back!" he shouted in the Other tongue. "Stay away!"

The Dasheter’s sails were furled, so he didn’t have to compete with their snapping, but the wind was in his face, stealing his words. "Go back!" he shouted again, and then, more plaintively, "Please! Please go back!"

The orange boats sliced through the water, approaching fast. Toroca thought about ordering the Dasheter’s sails unfurled, for rowboats were no match for a sailing ship, but by the time the ropes could be untied and the red leather sheets had billowed out, the Others’ boats would have already arrived.

Toroca stopped waving. Even if they couldn’t hear him, they could surely see him. He made go-away gestures with his left hand. He hoped the sign of pushing away was universal, but in his lessons with Jawn such things had never come up. "Go back!" he shouted again in the Other language.

It was no use. He looked down toward the deck and saw three red leather caps. "Get below," he shouted. "For God’s sake, get below."

The crewmembers were tarrying. They were curious about the Others, and perhaps doubted the stories of the effect the Others’ appearance would have on them. Still, respect for Toroca ran deep, and two of the three heeded his words, heading below. The third, farther away, perhaps couldn’t hear the order.

The nearer of the orange boats had now pulled up beside the Dasheter. From Toroca’s vantage point, he couldn’t see it at all, since the raised sides of his ship blocked it from view. He scurried down the ropes, getting a nasty burn on his right hand in doing so, and hurried toward the gunwale.

Below was Morb, the Others’ security chief, his black armbands stark against his yellow limbs. He was waving up at Toroca, and had his mouth open in that way that the Others considered to be friendly. "Go back!" shouted Toroca in the Other language. "Go back!"

Morb made a dismissive motion with his hand. "Nonsense!" he shouted up from the waves. "You have been out to visit us. It is time we did the same!"

Morb’s boat was bobbing on the waves alongside one of the Dasheter’s own shore boats; they’d been used for fishing while the Dasheter waited for Toroca. Morb had his hands on the rope ladder used to access these boats, a ladder that led up to the Dasheter’s foredeck.

"It is not safe!" shouted Toroca.

Morb’s tone was a bit sharper. "It is wrong for you to know all about us with us knowing almost nothing about you. I am coming aboard!" The Other began climbing. Toroca was near panic. In desperation, he brought his jaws down on the rope ends that tied the ladder to the gunwale. The rope was tougher than he’d expected. Some of his looser teeth popped out. He smashed his jaws together again, and this time did sever one of the two heavy lines. But Morb was already most of the way to the top.

Suddenly a green arm shot out from the Dasheter’s side, gripping Morb’s ankle. Toroca leaned over the gunwale and saw an open porthole on the deck immediately below. Someone had been watching through a window, had seen this Other as he passed by.

Morb twisted as the ladder, anchored now by only a single rope, swung madly to the left. He smashed his other foot down on the arm grabbing his ankle. Whoever was holding on screamed and let go. Morb took hold of the Dasheter’s gunwale just as Toroca brought his jaws together on the remaining rope anchoring the ladder. As before, two massive bites would be needed to sever the braided cord, but before Toroca could get his second bite in, Morb had hauled himself over the railing and was standing on the deck of the Dasheter.

Suddenly old Biltog appeared at the top of the ramp, his right arm bloodied and hanging limply at his side, but the rest of his body moving up and down, up and down, bobbing in full dagamant.

Toroca shouted, "Into the water, Morb! For your own safety, jump into the water."

Morb stared at Biltog for a moment, the murderous fury in the old sailor’s expression obvious to Toroca but apparently less clear to the Other. "What is wrong?" asked Morb.

Toroca caught a movement out of the corner of his eye. Something had sailed over the rear hull of the Dasheter. Ropes, metal hooks. The Others in the second boat had brought their own climbing equipment. Their ropes were pulled tight, and the hooks caught in the railing around the ship’s edge.

What to do? Push Morb over the side? Try to draw Biltog’s attention away from the Other? Or run to the rear of the Dasheter and try to dislodge the Others’ rope ladder before more boarded the ship?

And then, all at once…

Biltog charged…

Morb ran across the deck…

An Other appeared at the top of the ladder on the Dasheter’s rear hull…

And one more Other appeared at the top of the rope ladder adjacent to Toroca, anchored at only one side, half-severed but still holding.

Captain Keenir emerged at the mouth of another access ramp — too proud, too stubborn, too foolish to not try to intervene in what was happening…

Biltog intercepted Morb, leaping through the air, jaws split wide, landing on the Other’s back, the two of them smashing into the deck hard enough to rock the ship, Biltog’s jaws tearing into the Other’s spinal cord … Keenir caught sight of the Other at the top of the ladder near Toroca. The Other’s face was wide with terror and he quickly reversed himself, scrambling over the gunwale and grabbing at the damaged rope ladder. Keenir’s footfalls echoed like thunder. "Captain, no!" shouted Toroca, but Keenir was too deep in the bloodlust to heed any words.

The Other on the rope ladder was having a hard time getting down. The rope twisted and…

It snapped!

The Other and the rope ladder went crashing toward the waves.

Keenir, not to be deterred, leapt over the railing, diving down toward the water.

The Other below was flailing about, trying to make it to the orange boat.

Keenir sliced into the water. Toroca, gripping the railing, hoped that the impact would be enough to break the old mariner out of dagamant, but soon he was on the surface again, his muscular tail propelling him through the waves. Within moments he was upon the swimming Other, jaws digging into the Other’s neck, tearing it open. The water turned red.

Toroca pivoted and saw Biltog, his muzzle covered in blood, still bobbing up and down. The sailor began running toward Toroca, toeclaws splintering the wooden deck.

Biltog was substantially older than Toroca, much too strong for Toroca to fight. Toroca looked left and right, but he was trapped against the railing; Biltog could alter his course to intercept him no matter which way he decided to run. But suddenly Biltog was airborne, a giant leap pushing him up off the deck. It turned out that he wasn’t after Toroca, but rather had decided to join his captain. Biltog sailed over th

e edge of the ship, his red cap flying off, the tip of his tail slapping into Toroca’s head as it passed him. Toroca swung around. Biltog was in the water now, swimming toward the orange boat, which was trying to escape, the three remaining Others aboard it rowing with all their might.

Biltog chomped through an oar and then, grabbing the little boat’s side and pulling hard, he capsized the ship, tossing its occupants into the water.

Suddenly a large red stain began spreading across the waves. Keenir was out of sight; he must have come up on one of the Others from underneath, jaws tearing into its body. Biltog had another’s tail in his mouth. His jaws worked, muscles bulging, and the tail sheared off.

Pounding on the deck behind him.

Toroca swung around…

A ball of limbs and tails, some green, some yellow, locked in mortal combat. More Quintaglios had come up from below.

Toroca watched, helpless to intervene. Sounds of splitting bone and smashing teeth filled the air, punctuated by screams from both Others and Quintaglios.

He thought again of the story of the Galadoreter, blown aimlessly by the wind, its decks covered with the dead …

"Toroca!"

Deep, gravelly — Keenir’s voice, from over the side. Toroca looked over the edge. "Are you all right, Captain?"

Keenir was moving up and down, but with the bobbing of the waves, not in territorial display. "They’re all dead down here," he called, his tone aghast.

Biltog was floating next to him in the red water. And next to the two of them, five yellow carcasses bobbed up and down, in death returning the challenge.

"Stay down there!" Toroca shouted. "It’ll be safer!"

Behind him, the battle raged on, the planks of the deck slick with blood.

Looking over the gunwale, Toroca saw the second orange boat, off in the distance. Only two of its crew were still aboard, but they were already a good part of the way back to their island, where doubtless they’d report that their eight comrades had been torn limb from limb by the strange green visitors.

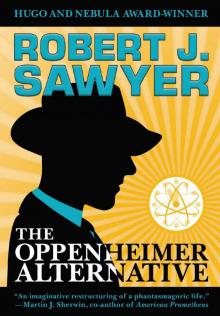

The Oppenheimer Alternative

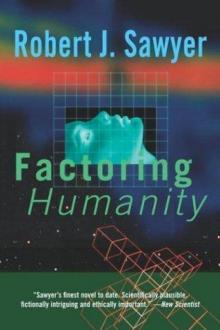

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

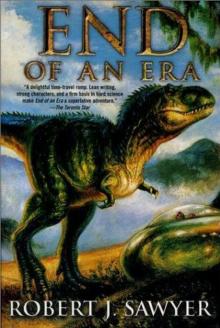

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time