- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

Illegal Alien Page 18

Illegal Alien Read online

Page 18

Clete’s voice could be heard to say, “It slices! It dices!”

“Pardon?” said Hask.

“A line from an old TV commercial—for the Ronco Veg-O-Matic. ‘It slices! It dices!’” Clete sounded impressed. “Purty neat device. But if you can’t see the thread, isn’t it dangerous?”

Hask grabbed the two parts of the handle and pulled them as far apart as he could. Every fifteen inches or so, a large blue bead appeared along the otherwise invisible filament. “The beads enable you to see the filament,” said Hask, “as well as letting you handle it safely. They are lined on the inside with a monomolecular weave that the filament cannot cut through, so you can slide the beads along the filament if they get in the way.” Hask’s tuft moved in a shrug. “It is a general-purpose tool, not just for carving meat; nothing sticks to the monofilament, so you do not have to worry about keeping it clean.”

Dale had his eyes glued to the jurors. First one got it, and then another, and soon they all had reacted with either widened eyes or noddings of their heads: they had just seen what could very likely have been the murder weapon.

Hask brought the two handles together—the molecular chain and its beads were reeled in as he did so—and he placed the unit back in a pocket. He then reached out with his front hand and plucked the floating disk of meat out of the air. Very little blood had been shed—a few circular drops had come free as the molecular chain went through the meat, but something—a vacuum cleaner, perhaps—had sucked them down into the Y-shaped support.

“What kind of critter is that?” said Clete. His arm was visible again, pointing at the skinless snake.

“It is not an animal,” said Hask. “It is meat.” The image bounced as Clete pushed off the wall to have a closer look at what Hask was holding. Clete apparently wasn’t good at maneuvering while weightless; Hask had to reach out with a leg—which bent in a way that would have snapped the joint had Hask been human—to stop Clete’s movement. Clete thanked Hask, then took a close-up shot of the piece of meat. It was clear now that it did have a skin, made up of diamond-shaped plates just like Hask’s own hide. But the skin on the meat was thin and crystal clear.

“Meat, but not an animal?” said Clete’s voice. He sounded perplexed.

“It is just meat,” Hask said. “It is not an animal. Rather, it is a product of genetic engineering. It has only what nervous system is required to support its circulatory system, and its circulatory system is simplicity itself. It is not alive; it feels no pain. It is simply a chemical factory, converting raw materials fed to it through the wall receptacle into edible flesh, balanced perfectly for our nutritional needs. Of course, it is not all we eat—we are omnivores, as you are.”

“Ah,” said Clete. “Y’all couldn’t bring animals on your long space voyage, but this lets y’all enjoy the taste.”

Hask’s front eyes blinked repeatedly. “We do not eat animals on our world,” he said. “At least, not anymore.”

“Oh,” said Clete. “Well, we don’t have the ability to create meat. We kill animals for their flesh.”

Hask’s tuft waggled as he considered this. “Since we do not have to kill for food, we no longer do so. Some say we have sacrificed too much—that killing one’s own food is a release, the outlet nature intended for violent urges.”

“Well, I’m an old country boy,” said Clete. “I’ve done my share o’ huntin’. But most people today, they get their meat prepackaged at a store. They don’t ever see the animal, and have no hand in the kill.”

“But you say you have killed?” said Hask.

“Well, yes.”

“What is it like—to kill for food?”

The camera bounced; Clete was apparently shrugging as he held it. “It can be very satisfying. Nothing quite so delicious as a meal you tracked and bagged yourself.”

“Intriguing,” said Hask. He looked at his disk of meat, as though it were somehow no longer all that appetizing. Still, he brought it to his front mouth, the outer horizontal and inner vertical openings forming a square hole. His rust-colored dental plates sliced a piece off the edge of the meat disk, and to the jury’s evident surprise, two long flat tongues popped out of the mouth after each bite, wiping what little blood there was from Hask’s face.

“You eat the meat raw?” said Clete.

Hask nodded. “In ancient times we cooked animal flesh, but the reasons for cooking—to soften the meat, and to kill germs—do not apply to this product. Raw meat is much more flavorful…”

“That’s fine,” said Linda Ziegler, rising in the darkness. The bailiff pushed the pause button, and a still image of the floating Tosok, holding the now half-eaten piece of raw flesh in his hand, jerked and flickered on the monitors. The lights in the courtroom were brought back to full illumination; jurors and audience members rubbed their eyes.

Linda Ziegler then introduced into evidence one of the Tosok monofilament tools—the one that had belonged to Hask. There was no way to demonstrate that it was the specific one that had been used in the murder; forensics had been unable to find any evidence of that, and so she didn’t bother pursuing this line of questioning.

Of course, Hask possessed a new monofilament tool now; the mothership had dozens in its stores. A smaller version of the Tosok meat factory had been installed at Paul Valcour Hall; Hask needed one of the tools in order to feed himself, and Dale had successfully argued that one accused of killing with a knife is normally not denied access to cutlery.

Still, there was no doubt that the shipboard videotape, and the presentation of Hask’s cutting tool in court, had a huge impact on the jury. And so, with smug satisfaction, Linda Ziegler returned to her seat and said, “Your Honor, the People rest.”

CHAPTER

23

Hask and Frank had returned with Dale to Dale’s twenty-seventh-floor office. As soon as they arrived, though, Hask excused himself to use the bathroom. Like humans, Tosoks eliminated both solid and liquid waste, and with some difficulty they could make use of human toilets.

Once Hask had left the room, Frank leaned forward in his usual easy chair. “Ziegler’s case was quite devastating,” he said. “What does our shadow jury say?”

Dale heaved his massive bulk into his leather chair and consulted a report Mary-Margaret had left on his desk. “As of this moment they’re voting unanimously to convict Hask,” he said with a sigh.

Frank frowned. “Look, I know you said we shouldn’t put Hask on the stand, but at this stage surely the real jury will be expecting to hear from him.”

“Possibly,” said Dale. “But Pringle will tell them that the defendant is under no obligation to testify; the entire burden is on prosecution. That’s part of CALJIC. Still…”

“Yes?”

“Well, this is hardly a normal case. You know what it says in the charge—‘did willfully, unlawfully, and with malice aforethought murder Cletus Robert Calhoun, a human being.’ In previous cases, it always seemed funny to me that they specify ‘a human being,’ but that is the key point in this case. The deceased is human, and the defendant is not—and the jury might well feel the prosecution has less of a burden in this case.” He waved the report at Frank. “That seems to be what our shadow jury is saying, anyway: if they make the wrong verdict, well, it’s not as though a human being would end up rotting in jail. If we can put Hask on the stand, and convince the jury that he’s every bit as much a person, every bit as real and sensitive as anyone else, then they may decide the way we want them to. The key, though, is to get them to like Hask.”

“That’s not going to be easy,” said Frank, shaking his head. Late-afternoon sunlight was painting the room in sepia tones. “I mean, we can’t win the jurors over with Hask’s smile, or anything like that—he physically can’t smile, and frankly, those rusty dental plates give me the willies. And shouldn’t a good defendant show more horror when crime-scene photos are displayed? I was hoping the Tosok taboo about internal matters would have worked in our favor there, but a

ll Hask did was wave that topknot around in various patterns. The jury will never understand what those mean.”

“Don’t underestimate juries,” said Dale. “They’re a lot smarter than you might think. I’ll give you an example: I once handled a personal-injury case; not my normal thing, but it was for a friend. Our position was that the reason the person had been injured was because the car’s seat belt was faulty. Well, during our case, every time I mentioned that, I took off my glasses.” He demonstrated. “See? After I’d done that a few dozen times, the jury was conditioned. Then, whenever the automaker’s lawyer tried to point out alternative possible causes for the accident, I’d just take off my glasses. Never said a word, see, and there’s nothing in the transcript. But I’d take off my glasses, and the jury would be reminded of the faulty seat belt. We won 2.8 million in that case.”

“Wow.”

“If the jury can learn that ‘glasses coming off’ means ‘defective seat belt,’ it can also learn that ‘topknot waving side to side’ means Tosok laughter, or that ‘topknot lying flat’ means Tosok revulsion. Don’t worry, son. I think our jury knows Hask and the other Tosoks a lot better than you think they do.”

“So then we should put Hask on the stand.”

“Maybe…but it still worries me. Nine times out of ten, it’s a disaster, and—”

The door to Dale’s office opened, and Hask strode in. “I wish to testify,” he said at once, lowering his weight onto the single Tosok chair.

Dale and Frank exchanged glances. “I advise against it,” said Dale.

Hask was silent for a moment. “It is my decision to make.”

“Of course, of course,” said Dale. “But you’ve never seen a criminal case before; I’ve seen hundreds. It’s almost always a mistake for the defendant to take the stand.”

“Why? What chance is there that they will find me innocent if I do not testify?”

“No one ever knows what a jury is thinking.”

“That is not true. Your shadow jury has already voted to convict me, has it not?”

“No, it hasn’t.”

“You are lying.”

Dale nodded. “All right, all right. But even if it has, taking the stand is almost always the wrong move. You only do that when you have no other choice.”

“Such as now,” said Hask. As always, his natural voice rose as the words were spoken, making it impossible to tell if it was a question or a statement.

Dale sighed again. “I suppose. But you know that Linda Ziegler will get to cross-examine you?”

“I understand that.”

“And you still want to do it?”

“Yes.”

“All right,” said Dale, resigning himself to it. “But we’ll put you on the stand first.”

“Why first?” asked Hask.

“Because if Linda eviscerates you—forgive the metaphor—we’ll have the rest of our case-in-chief to try to recover.” Dale scratched his chin. “We should talk about your testimony—figure out what you’re going to say.”

“I am going to tell the truth, of course. The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.”

Dale raised his eyebrows. “Really?”

“You cannot tell, can you?” said Hask.

“Tell that you’re innocent? Of course I believe that, Hask, but—”

“No, tell if I am telling the truth.”

“What? No. Aren’t you?”

Hask fell silent.

There was an even bigger-than-normal crowd of reporters outside the Criminal Courts Building the next morning. Many dozens of reporters shouted questions at Dale and Frank as they entered, but Dale said nothing. Inside the courtroom, the excitement was palpable.

Judge Pringle came in, said her usual good morning to the jurors and lawyers, and then looked at Dale. “The defense may now begin its case-in-chief,” she said.

Dale rose and moved to the lectern. He paused for a moment, letting the drama build, then, in that Darth Vader voice of his, he boomed out, “The defense calls Hask.”

The courtroom buzzed with excitement. Reporters leaned forward in their chairs.

“Just a second,” said Judge Pringle. “Hask, you are aware that you have an absolute constitutional right not to testify? No one can compel you to do so, if it is not your wish?”

Hask had already arisen from his special chair at the defense table. “I understand, Your Honor.”

“And no one has coerced you into testifying?”

“No one. In fact—” He fell silent.

Dale kept an expressionless face, but was relieved. At least he’d taught Hask something. He’d closed his mouth before he’d said “In fact, my lawyer advised me against testifying,” thank God.

“All right,” said Pringle. “Mr. Ortiz, please swear the witness in.” Hask made his way to the witness stand. As he did so, a court worker removed the human chair and replaced it with a Tosok one.

“Place your front hand on the Bible, please.” Hask did so. “You do solemnly swear or affirm,” said the clerk, “that the testimony you may give in the cause now pending before this Court shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?”

“I do so affirm,” said Hask.

“Thank you. Be seated, and please state and spell your name for the record.”

“Hask, which I guess is H-A-S-K.”

“Mr. Rice,” said Judge Pringle, “you may proceed.”

“Thank you, Your Honor,” said Dale, slowly getting to his feet and making his way to the lectern. “Mr. Hask, what is your position aboard the Tosok starship?”

“My title was First.”

“‘First’—is that like ‘first officer’?”

“No. The First is the person who comes out of hibernation first. It was my job to deal with any in-flight emergencies, and also to be the first revived upon arrival at our destination, in order to determine if it was safe to revive the others.”

“So you are a very important member of the crew?”

“On the contrary, I am the most expendable.”

“The prosecution has suggested you had the opportunity to kill Dr. Calhoun. Did you have that opportunity?”

“I was not alone with him at the time he died.”

“But you can’t account for your presence during the entire window of opportunity for this crime.”

“I can account for it. I simply cannot prove the truth of the account. And there are others who had equal opportunity.”

“The prosecution has also suggested that you had the means to kill Dr. Calhoun. Specifically, that you used a monofilament carving tool to sever his leg. Would such a tool work for that purpose?”

“I suspect so, yes.”

“But a murder conviction requires more than just opportunity and means. It—”

“Objection. Mr. Rice is arguing his case.”

“Sustained.”

“What about motive, Hask? Did you have any reason to want to see Dr. Calhoun dead?”

Ziegler was on her feet. “Objection, Your Honor. CALJIC 2.51: ‘Motive is not an element of the crime charged and need not be shown.’”

“Overruled. I’ll present the jury instructions, counselor.”

“Hask, did you have any motive for wanting to see Dr. Calhoun dead?”

“None.”

“Is there any Tosok religious ritual that involves dissection or dismemberment?”

“No.”

“We humans have some rather bloody sports. Some humans like to hunt animals. Do your people hunt for sport?”

“Define ‘for sport,’ please.”

“For fun. For recreation. As a way of passing the time.”

“No.”

“But you are carnivores.”

“We are omnivores.”

“Sorry. But you do eat meat.”

“Yes. But we do not hunt. Our ancestors did, certainly, but that was centuries ago. As the Court has seen, we now grow meat that has no central ne

rvous system.”

“So you’ve never had the urge to kill something with your own hands?”

“Certainly not.”

“The tape we saw of you and Dr. Calhoun talking aboard the mothership implies differently.”

“I was engaging in idle speculation. I said something to the effect that perhaps we had given up too much in no longer hunting our own food, but I have no more desire to slaughter something to eat than you do, Mr. Rice.”

“In general, is there any reason at all you’d want to kill something?”

“No.”

“In particular, is there any reason you’d want to kill Dr. Calhoun?”

“None whatsoever.”

“What did you think of Dr. Calhoun?”

“I liked him. He was my friend.”

“How did you feel when you learned he was dead?”

“I was sad.”

“Reports say you didn’t look sad.”

“I am physically incapable of shedding tears, Mr. Rice. But I expressed it in my own way. Clete was my friend, and I wish more than anything that he was not dead.”

“Thank you, Mr. Hask.” Dale sat down. “Your witness, counselor.”

“Hask,” said Ziegler, rising to her feet.

“Your Honor,” said Dale, “objection! Mr. Hask is entitled to common courtesy. Ms. Ziegler should surely precede his name with an honorific.”

Ziegler looked miffed, but apparently realized that any argument would just make her look even more rude.

“Sustained,” said Pringle. “Ms. Ziegler, you will address the defendant as ‘Mr. Hask’ or ‘sir.’”

“Of course, Your Honor,” said Ziegler. “My apologies. Mr. Hask, you said you weren’t alone with Dr. Calhoun at the time of his murder.”

“Correct.”

“But you had been alone with him on other occasions?”

“Certainly. We took the trip up to the mothership together.”

“Yes, yes. But, beyond that, hadn’t you and he spent time alone at the USC residence?”

“From time to time he and I happened to be the only people present in a given room.”

“It was more than that, wasn’t it? Is it not true that you often spent time alone with Dr. Calhoun—sometimes in his room at Valcour Hall, sometimes in your own?”

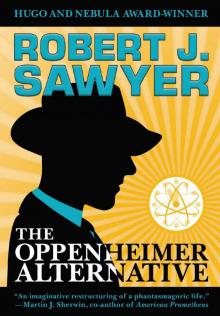

The Oppenheimer Alternative

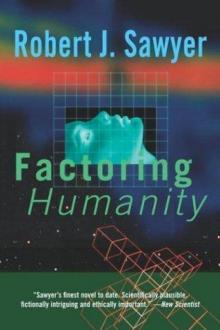

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

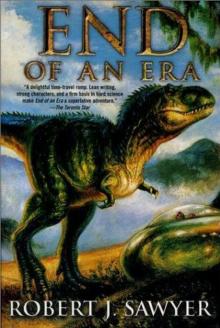

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time