- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

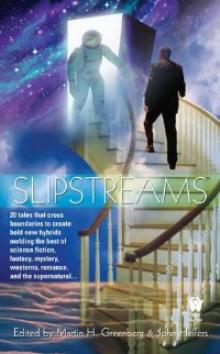

Hybrids Page 2

Hybrids Read online

Page 2

“Jock?”

Jock usually kept his door open-that was good management, wasn’t it? An open-door policy? Still, he was startled to see a Neanderthal face-broad, browridged, bearded-peeking around the jamb. “Yes, Ponter?”

“Lonwis Trob brought along some communiqués from New York City.” Lonwis and the nine other famous Neanderthals, plus the Neanderthal ambassador, Tukana Prat, had been spending most of their time at the United Nations. “Are you aware of the Corresponding-Points trip?”

Jock shook his head.

“Well,” said Ponter, “you know there are plans to open a bigger, permanent, ground-level portal between our worlds. Apparently your United Nations has taken the decision that the portal should be between United Nations headquarters and the corresponding point on my world.”

Jock frowned. Why the hell was he getting intelligence reports from a bloody Neanderthal? Then again, he hadn’t yet checked his own e-mail today; maybe it was there. Of course, he’d known that the New York City option was being considered. It was a no-brainer, as far as Jock was concerned: obviously the new portal should be on U.S. soil, and putting it at United Nations Plaza-technically international territory-would appease the rest of the world.

“Lonwis says,” continued Ponter, “that they are planning to take a group of United Nations officials over to the other side-myside. Adikor and I are going to go down to Donakat Island-our version of Manhattan-with them, to survey the site; there are considerable issues related to shielding any large-size quantum computer from solar, cosmic, and terrestrial radiation, lest decoherence occur.”

“Yes? So?”

“Well, so, I thought perhaps you might like to come along? You run this institute devoted to establishing good relations with my world, but you have not yet seen it.”

Jock was taken aback. He found having two Neanderthals here at Synergy just now rather creepy; they looked so much like trolls. He wasn’t sure he wanted to go somewhere where he’d be surrounded by them. “When’s this trip happening?”

“After the next Two becoming One.”

“Ah, yes,” said Jock, trying to keep up a pleasant facade. “I believe our Louise’s phrase for that is, ‘Par-tay!’ “

“There is much more to it than that,” said Ponter, “although you will not get to see it on this proposed trip. Anyway, will you join us?”

“I’ve got a lot of work to do,” said Jock.

Ponter smiled that sickening foot-wide smile of his. “It is my kind that is supposed to lack the desire to see beyond the next hill, not yours. You should visit the world you are dealing with.”

Ponter came up to Mary’s office and closed the door behind him. He took Mary in his massive arms, and they hugged tightly. Then he licked her face, and she kissed his. But at last they let each other go, and Ponter’s voice was heavy. “You know I have to return to my world soon.”

Mary tried to nod solemnly, but she apparently was unable to completely suppress her grin. “Why are you smiling?” asked Ponter.

“Jock has asked me to go with you!”

“Really?” said Ponter. “That is wonderful!” He paused. “But of course...”

Mary nodded and raised a hand. “I know, I know. We will only see each other four days a month.” Males and females lived largely separate lives on Ponter’s world, with females inhabiting the city centers, and males making their homes out at the rims. “But at least we’ll be in the same world-and I’ll have something useful to do. Jock wants me to study Neanderthal biotechnology for a month, learn all that I can.”

“Excellent,” said Ponter. “The more cultural exchange, the better.” He looked briefly out the window at Lake Ontario, perhaps envisioning the trip he would soon have to take. “We must head up to Sudbury, then.”

“It’s still ten days until Two become One, isn’t it?”

Ponter didn’t have to check his Companion; of course he knew the figure. His own woman-mate, Klast, had succumbed to leukemia two years ago, but it was only when Two were One that he got to see his daughters. He nodded. “And after that, I am to head down south again, but in my world-to the site that corresponds to United Nations headquarters.” Ponter never said “UN”; the Neanderthals had never developed a phonetic alphabet, and so the notion of referring to something by initials was completely foreign to them. “The new portal is to be built there.”

“Ah,” said Mary.

Ponter raised a hand. “I won’t leave for Donakat until this next Two becoming One is over, of course, and I’ll be back long before Two become One once again.”

Mary felt some of her enthusiasm draining from her. She’d known intellectually that even if she was in the Neanderthal world, twenty-five days would normally pass between times when she could be in Ponter’s arms, but it was a hard concept to get used to. She wished there was a solution, somewhere, in some world, that would see her and Ponter always together.

“If you are going back,” said Ponter, “then we can travel to the portal together. I was going to get a lift with Lou, but...”

“Louise? Is she going over, too?”

“No, no. But sheis going to Sudbury the day after tomorrow to visit Reuben.” Louise Benoît and Reuben Montego had become lovers while they were quarantined together, and their relationship had continued afterward. “Say,” said Ponter, “if all four of us are going to be in Sudbury at the same time, perhaps we can have a meal together. I have been craving Reuben’s barbecues...”

Mary Vaughan currently had two homes on her version of Earth: she had been renting a unit at Bristol Harbour Village here in upstate New York, and she owned a condominium apartment in Richmond Hill, just north of Toronto. It was to that latter home that she and Ponter were now heading-a three-and-a-half-hour drive from Synergy Group headquarters. Along the way, once they’d gotten off the New York State Thruway in Buffalo, they’d stopped for KFC-Kentucky Fried Chicken. Ponter thought it was the greatest food ever-a sentiment Mary didn’t disagree with, much to her waistline’s detriment. Spices were a product of warm climates, designed to mask the taste of meat that was off; Ponter’s people, who lived in high latitudes, didn’t use much in the way of seasonings, and the combination of eleven different herbs and spices was unlike anything he’d ever had before.

Mary played CDs on the long drive; it beat constantly hunting for different stations as they moved along. They’d started with Martina McBride’sGreatest Hits , and were now listening to Shania Twain’sCome On Over . Mary liked most of Shania’s songs, but couldn’t stand “The Woman In Me,” which seemed to lack the signature Twain oomph. She supposed she could get ambitious someday and burn her own CD of the album, leaving that song out.

As they drove along, the music playing, the sun setting-as it did so early at this time of year-Mary’s thoughts wandered. Editing CDs was easy. Editing a life was hard. Granted, there were only a few things in her past that she wished she could edit out. The rape, certainly-had it really only been three months ago? Some financial blunders, to be sure. Plus a handful of misspoken remarks.

But what about her marriage to Colm O’Casey?

She knew what Colm wanted: for her to declare, in front of her Church and God, that their marriage had never really existed. That’s what an annulment was, after all: a refutation of the marriage, a denying that it had even happened.

Surely someday the Roman Catholic Church would end its ban on divorce. Until Mary had met Ponter, there’d been no particular reason to wrap up her relationship with Colm, but now shedid want to get it over with. And her choices were either hypocrisy-seeking an annulment-or excommunication, the penalty for getting a divorce.

Ironic, that: Catholics could get off the hook for any venial sin just by confessing it. But if you’d by chance married the wrong person, there was no easy recourse. The Church wanted it to be until death do you part-unless you were willing to lie about the very fact of the marriage.

And, damn it all, her marriage to Colm didn’t deserve to be wiped out,

to be expunged, to be eradicated from the records.

Oh, she hadn’t been 100 percent sure when she’d accepted his proposal, and she hadn’t been completely confident when she’d walked down the aisle on her father’s arm. But the marriagehad been a good one for its first few years, and when it had gone bad it had only done so through changing interests and goals.

There had been much talk of late about the Great Leap Forward, when true consciousness had first emerged on this world, 40,000 years ago. Well, Mary had had her own Great Leap Forward, realizing that her desires and career ambitions didn’t have to take a back seat to those of her lawfully wedded husband. And, from that moment on, their lives had diverged-and now they were worlds apart.

No, she would not deny the marriage.

And that meant...

That meant getting a divorce, not an annulment. Yes, there was no law that said a Gliksin-the Neanderthals’ term for aHomo sapiens -who was still legally married to another Gliksin couldn’t undergo the bonding ceremony with a Barast of the opposite sex, but someday, doubtless, there would be such laws. Mary wanted to commit wholeheartedly to Ponter as his woman-mate, and doing that meant bringing a final resolution to her relationship with Colm.

Mary passed a car, then looked over at Ponter. “Honey?” she said.

Ponter frowned ever so slightly. It was an endearment that Mary used naturally, but he didn’t like it-because it contained theee phoneme that his mouth was incapable of making. “Yes?” he said.

“You know we’re going to spend the night at my place in Richmond Hill, right?”

Ponter nodded.

“And, well, you also know that I’m still legally bonded to my...my man-mate here, in this world.”

Ponter nodded again.

“I-I would like to see him, if I can, before we head off from Richmond Hill to Sudbury. Maybe have breakfast with him, or an early lunch.”

“I am curious to meet him,” said Ponter. “To know what sort of Gliksin you chose...”

The CD changed to a new track: “Is There Life After Love?”

“No,” said Mary. “I mean, I need to see him alone.”

She looked over and saw Ponter’s one continuous eyebrow rolling up his browridge. “Oh,” he said, using the English word directly.

Mary returned her gaze to the road ahead. “It’s time I settled things with him.”

Chapter Three

“I said it during my campaign, and I say it again now: a president should be forward-thinking, looking not just to the next election but to decades and generations to come. It is with that longer view in mind that I speak to you tonight...”

Cornelius Ruskin lay in his sweat-soaked bed. He lived in a top-floor apartment in Toronto’s seedy Driftwood district-his “penthouse in the slums,” as he’d called it back when he’d been in the mood to make jokes. Sunlight was streaming in around the edges of the frayed curtains. Cornelius hadn’t set an alarm-not for the last several days-and he didn’t feel energetic enough to roll over and look at his clock.

But the real world would soon intrude. He couldn’t remember the exact details of the sick benefits he was entitled to as a sessional instructor-but whatever they were, doubtless, after a certain number of days, the university, the union, the union’s insurer, or all three of them, would require a doctor’s certificate. So, if he didn’t go back to teaching, he wouldn’t get paid, and if he didn’t get paid...

Well, he had enough to cover the rent for next month, and, of course, he’d had to pay the first and last months’ rent in advance, so he could stay here until the end of the year.

Cornelius forced himself not to reach down and feel for his balls once more. They were gone; he knew they were gone. He was coming toaccept that they were gone.

Of course, there were treatments: men lost testicles because of cancer all the time. Cornelius could go on testosterone supplements. No one-in his public life at least-would ever have to know that he was taking them.

And his private life? He didn’t have one-not anymore, not since Melody had broken up with him two years ago. He’d been devastated, even suicidal for a few days. But she’d graduated from Osgoode Hall-York University’s lawschool-finished articling, and was sliding into a $180,000-a-year associate’s position at Cooper Jaeger. He could never have been the kind of power-husband she needed, and now...

And now.

Cornelius looked up at the ceiling, feeling numb all over.

Mary hadn’t seen Colm O’Casey for many months, but he looked perhaps five years older than she remembered him. Of course, she usually thought of him as he’d been back when they were living together, when they’d been planning jointly for eventual retirement, already having set their hearts on a country house on B.C.’s Salt Spring Island...

Colm rose as Mary approached, and he leaned in to kiss her. She turned her head, offering only her cheek.

“Hello, Mary,” he said, sitting back down. There was something surreal about a steakhouse at lunchtime: the dark wood, the imitation Tiffany lamps, and the lack of windows all made it seem like night. Colm had already ordered wine-L’ambiance, their favorite. He poured some in the waiting glass for Mary.

She made herself comfortable-as comfortable as she could-and sat in the chair across the table from Colm, a candle in a glass container flickering between them. Colm, like Mary, was a bit on the pudgy side. His hairline had continued its retreat, and his temples were gray. He had a small mouth and a small nose-even by Gliksin standards.

“You’ve certainly been in the news a lot lately,” said Colm. Mary was on the defensive already, and opened her mouth to reply curtly but before she could, Colm raised a hand, palm out, and said, “I’m happy for you.”

Mary tried to remain calm. This was going to be difficult enough without her getting emotional. “Thanks.”

“So what’s it like?” Colm asked. “The Neanderthal world, I mean?”

Mary lifted her shoulders a bit. “Like they say on TV. Cleaner than ours. Less crowded.”

“I’d like to visit it someday,” said Colm. But then he frowned and added, “Although I don’t suppose I’ll ever get the chance. I can’t quite see them inviting anyone with my academic specialty there.”

That much was probably true. Colm taught English at the University of Toronto; his research was on those plays putatively by Shakespeare for which authorship was disputed. “You never know,” said Mary. He’d spent six months of their marriage on sabbatical in China, and she’d never have expected the Chinese to care about Shakespeare.

Colm was almost as distinguished in his field as Mary was in hers-nobody wrote aboutThe Two Noble Kinsmen without citing him. But, despite their ivory-tower lives, real-world concerns had intruded early on. Both York and U of T compensated professors on a market-value basis: law professors were paid a lot more than history professors because they had many other job opportunities. Likewise, these days-especiallythese days-a geneticist was a hot commodity, whereas there were few employment prospects outside academe for English-literature experts. Indeed, one of Mary’s friends used this tag at the end of his e-mails:

The graduate with a science degree asks, “Why does it work?” The graduate with an engineering degree asks, “How does it work?” The graduate with an accounting degree asks, “How much will it cost?” The graduate with an English degree asks, “Do you want fries with that?”

That Mary had been the real breadwinner had been only one of the sources of friction in their marriage. Still, she shuddered to think how he’d react if she told him how much the Synergy Group was paying her.

A female server came, and they ordered: steakfrites for Colm; perch for Mary.

“How are you liking New York?” asked Colm.

For half a second, Mary thought he meant New YorkCity , where Ponter had been shot in the shoulder back in September by a would-be assassin. But, no, of course he meant Rochester, New York-Mary’s supposed home now that she was working for the Synergy Group. “It’s nice,�

�� she said. “My office is right on Lake Ontario, and I’ve got a great condo on one of the Finger Lakes.”

“Good,” said Colm. “That’s good.” He took a sip of wine, and looked at her expectantly.

For her part, Mary took a deep breath. She’d been the one who’d called this meeting, after all. “Colm...” she began.

He set down his wineglass. They’d been married for seven years; he doubtless knew he wasn’t going to like what she had to say when she used that tone.

“Colm,” Mary said again, “I think it’s time that we...that we wrapped up unfinished business.”

Colm knit his brow. “Yes? I thought we’d settled all the accounts...”

“I mean,” said Mary, “it’s time for us to make our...the separation permanent.”

The server took that inopportune moment to arrive with salads: Caesar for Colm, mixed field greens with raspberry vinaigrette for Mary. Colm shooed the server away when she offered ground pepper, and he said, in a low volume, “You mean an annulment?”

“I...I think I’d prefer a divorce,” Mary said, her voice soft.

“Well,” said Colm. He looked away, at the fireplace on the far side of the dining room, the hearth stone cold. “Well, well.”

“It just seems time, that’s all,” said Mary.

“Does it?” said Colm. “Why now?”

Mary frowned ruefully. If there was one thing that studying Shakespeare inculcated in you, it was that there were always undercurrents and hidden agendas; nothing ever just happened. But she wasn’t quite sure how to phrase it.

No-no, that wasn’t true. She’d rehearsed the wording over and over in her head on the way here. It was his reaction she was unsure of.

“I’ve met somebody new,” Mary said. “We’re going to try to make a life together.”

Colm lifted his glass, took another sip of wine, then picked up a small piece of bread from the basket the waitress had brought with the salads. A mock communion; it said all that needed to be said. But Colm underscored the message with words anyway: “Divorce means excommunication.”

The Oppenheimer Alternative

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time