- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Page 4

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Read online

Page 4

"I’m sorry," said Babnol. "I cast a…"

Delplas held up her hand. "If you really want to cast something near me," she said, "let it be a net. The waters are rough here, but the fishing is excellent nonetheless. Do you like fish, Babnol?"

"I’ve rarely had any; I’m from an inland Pack."

"Well, then you’ve only had freshwater fish. Wait till you taste true River fish!"

Babnol dipped her head. "I’m looking forward to it."

The four of them began to amble down the beach. "You’ll meet the other four surveyors later," Toroca said to Babnol. Then he turned to face Delplas. "Babnol is an experienced fossil hunter," said Toroca.

"Whom did you study under?" asked Delplas.

"I’m self-taught," said Babnol, her head once again tilted up in that haughty way.

Delplas turned toward Toroca, her face a question.

"She’s not a trained geologist," he said, "but she’s very experienced. And she’s eager to learn."

Delplas considered for a moment, then: "Would that more of our people shared your passion for learning, Babnol." She bowed deeply. "Welcome to the Geological Survey of Land."

"I’m delighted to be a part of it," Babnol replied warmly.

"You’ll be even more delighted when you see what wonders we’ve found," said Toroca. He faced Spalton. "Still nothing below the Bookmark layer?"

"Nothing. We’ve taken thousands of samples, and still not a single find."

"The Bookmark layer?" said Babnol.

"Come," said Toroca. "We’ll show you."

They hiked farther along the beach, a few wingfingers circling overhead, and a crab occasionally scuttling across their path. Streamers of waterweeds were strewn here and there along the sands. At last they came to a small encampment consisting of a cluster of eleven small tents made out of thunderbeast hide arranged in a loose circle. A semicircular wall of stones had been built to shield them from the wind.

"This is home, at least for the next few dekadays," said Toroca. "After that, we’ll be heading to the south pole by sailing ship; we’ve recently requisitioned one for that journey. I don’t know which ship Novato will send, but I’m sure it will be a major vessel."

Babnol nodded.

The cliffs rose up in front of them. Babnol hadn’t been aware that her tail had been swishing back and forth to generate heat until they got here, in the lee of the stone crescent, and it suddenly stopped moving. Out of the biting wind, it was actually fairly pleasant. The sun was even peeking out from behind the clouds now.

Toroca gestured at the cliff, and Babnol let her eyes wander over its surface. She was startled to realize that way, way up the face, there were two Quintaglios, looking like tiny green spiders. "Those are two more members of our team," said Toroca. "You’ll meet them later."

"What are they doing?" said Babnol.

"Looking for fossils," said Toroca.

"And is the looking good here?"

"Depends," said Toroca, a mischievous tone in his voice. "I can tell you right now that Tralen — that’s the fellow higher up the cliff face — will find plenty, but Greeblo, the one lower down, will come up empty-handed."

"I don’t understand," said Babnol.

"Do you know what superposition is?" asked Spalton.

Babnol shook her head.

"My predecessor, Irb-Falpom, spent most of her life developing the theory of it," said Toroca. "It seems intuitively obvious once it’s explained, but until Falpom, no one had understood it." He gestured at the cliff. "You see the layers of rock?"

"Yes," said Babnol.

"There are two main types of rock: uprock and downrock. Uprock is thrust up from the ground as lava. Basalt is an uprock."

She nodded.

"But rain and wind and the pounding of waves cause uprock to crumble into dust. That dust is carried down to the bottom of rivers and lakes and gets compressed into downrocks, such as shale and sandstone."

"All right."

"Well, Falpom made the great leap: she realized that when you look at downrock layers, like the sandstone of these cliffs, the layers on the bottom are the oldest and the ones on the top are the youngest."

"How can that be?" said Babnol. "I thought all rocks came from the second egg of creation."

"That’s right, but they’ve changed in the time since that egg hatched. The way the rocks look today isn’t the way they were when the world was formed."

She looked skeptical, but let him continue.

"It’s really very simple," said Toroca. "I don’t know whether you’re a tidy person or not. I’m a bit of a slob myself, I’m sorry to say. My desk back in Capital City is covered with writing leathers and books. But I know if I’m looking for something I put on my desk recently, it will be near the top of the clutter, whereas something I set down dekadays ago will be near the bottom. It’s the same with rock layers."

"All right," said Babnol.

"Well, the rock layers we see here are the finest sequence in all of Land. The height of the cliffs from top to bottom represents an enormous span of kilodays, with the rock layers at the bottom representing truly ancient times."

"Uh-huh."

He pointed again. "You see that all the lower layers are brown or gray. If you look up, way, way up, almost nine-tenths of the way to the top, you’ll find the first layer that’s white. See it? Just a thin line?"

"Not really."

"We’ll climb up tomorrow, and I’ll show you. The layer in question is still a good fifteen paces from the top, of course, this being a big cliff, but — ah!" Spalton had disappeared a few moments ago into one of the tents and had now emerged holding a brass tube with an ornate crest on one end. "Thank you, Spalton," said Toroca, taking the object.

"A far-seer," said Babnol, her voice full of wonder. "I’ve heard of them, but never seen one up close."

"Not just any far-seer," said Delplas, jerking her head at the instrument Toroca now held. "That’s the one Wab-Novato gave to Sal-Afsan the morning after Toroca was conceived."

Toroca looked embarrassed. "It meant a great deal to my father," he said, "but once he was blinded, he could no longer use it. He wanted it to still be employed in the search for knowledge, and gave it to me when I embarked on my first expedition as leader of the Geological Survey." He proffered the device to Babnol.

She took it reverently, held the cool length in front of her with both hands, felt its weight, the weight of history. "Afsan’s far-seer…" she said with awe.

"Go ahead," said Toroca. "Put it to your eye. Look at the cliff."

She raised the tube. "Everything looks tiny!" she said.

Clicking of teeth from Spalton and Delplas. "That’s the wrong end," said Toroca gently. "Try it the other way."

She reversed the tube. "Spectacular!" She turned slowly through a half-circle. "That’s amazing!"

"You can sharpen the image by rotating the other part," Toroca said.

"Wonderful," breathed Babnol.

"Now, look at the cliff face."

She turned back to the towering wall of layered downrock. "Hey! There’s — what did you say his name was?"

"If it’s the fellow in the blue sash, it’s Tralen."

"Tralen, yes."

"All right. Scan up the cliff face until you come to a layer of white rock. Not light brown, but actual white. You can’t miss it."

"I don’t — wait a beat! There it is!"

"Right," said Toroca. "That’s what we call the Bookmark layer. It’s white because it’s made of chalk. There are no chalk layers below it because there are no shells of aquatic animals below it."

Babnol lowered the far-seer. "I don’t see the connection."

"Chalk is made of fossilized shells," said Delplas. "We often find beautiful shell pieces in chalk layers."

"Oh. We have no chalk in Arj’toolar. Lots of limestone, though — which is also made from shells."

Delplas nodded. "That’s right."

"But here," said Toroc

a, "there are no fossil shells below that first white layer." He leaned forward. "In fact, there are no fossils of any kind beneath that first white layer."

Babnol lifted the far-seer again, letting her circular view slide up and down the cliff face. "No fossils below," she said slowly.

"But plenty above," said Toroca. "There’s nothing gradual about it. Starting with that white layer, and in every subsequent layer, the rock is full of fossils."

"Then the — what did you call it? — the Bookmark layer…"

Toroca nodded. "The Bookmark layer marks the point in our world’s history at which life was created. Drink in the sight, Babnol. You’re seeing the beginning of it all!"

*6*

A Quintaglio’s Diary

I get tired of spending time with my siblings. It’s strange, because I have no idea how I should react. With others, my territorial instinct seems to operate properly. I know, without thinking, when I should get out of someone’s way and when I can reasonably expect someone to yield to me. But with my brothers and sisters, it’s different. Sometimes I feel as though their presence, no matter how close, doesn’t bother me in the least. At other times, I find myself challenging their territory for no good reason at all. That they are exactly the same age as me — neither younger nor older, neither bigger nor smaller — makes all standard protocols based on age and size meaningless.

It’s confusing, so very confusing. I wish I knew how to behave.

Rockscape, near Capital City

It was an eerie place, a place of the dead.

Ancient cathedral, ancient cemetery, ancient calendar — the debates raged on among the academics. All that remained were ninety-four granite boulders, strewn — or so it seemed at first glance — across a field of tall grasses, a field that ended in a sheer drop, edged with crumbling marl, plummeting to the great world-spanning body of water far below.

But the boulders, as one could clearly see when their positions were plotted, were not strewn. They were arranged, laid out in geometric patterns, lines drawn between them forming hexagons and pentagons, triangles, and perfect squares.

Rockscape, it was called: a minor tourist attraction, a site that most first-time visitors to Capital City made sure to see, proof that long before the current city had been built, Quintaglios had inhabited this area. Some claimed the rocks represented sacrificial altars on which the earliest Lubalites had practiced their cannibalistic ways. That was an easy theory to believe. The wind sometimes shrieked across the field like the doleful wails of those offered up to placate a God who was making the land tremble.

Afsan often came here, straddling a particular boulder, the one the historians referred to as Sun/Swift-Runner/4 but that everyone else had come to call simply Afsan’s rock. This was his place, a place for quiet contemplation, introspection, and deep thought.

Afsan could find his way here as easily at night as in the day, but he never did so. Indeed, he rarely came out at all after sunset. It was unbearable for him. To know that the stars — the glorious, glorious stars — were arching overhead was too much. Of all the sights he would never see again, Afsan missed the night sky most.

The great landquake of kiloday 7110 had left much of Capital City in ruins. In its aftermath, most of the Lubalites had gone into hiding again. Officially, no record was kept of who had been identified as a member of that ancient sect, and even unofficially little concern was paid to it. Oh, there were those who called for retribution, but Dybo declared an amnesty. After all, when he made the public announcement that he agreed with Afsan that Larsk was a false prophet, he couldn’t very well penalize those who had refused to worship Larsk earlier. Jal-Tetex was permitted to remain on as imperial hunt leader, although she died eventually, in exactly the way she would have liked to — on the hunt. The lanky Pal-Cadool stayed in favor with the palace, although he was reassigned from being chief butcher to personal assistant to Afsan, a role he had unofficially held anyway since the blinded Afsan had been released from prison.

Afsan, whom some had called The One, the hunter foretold by Lubal, who would lead the Quintaglios on the greatest hunt of all.

Some still believed Afsan to be this — and, indeed, some took the exodus to be the hunt Lubal had spoken of. Others who had believed it once, had grown less and less convinced of it as time went by. Afsan, after all, had not hunted in kilodays. And others still, of course, had always scoffed at the suggestion that Afsan was The One.

Cadool did his best to make Afsan’s life comfortable. Afsan often sent Cadool to run errands or do things that he could not himself, and that meant that Afsan was often alone.

Alone, that is, except for Gork.

"It’ll help look after you," Cadool had said. Afsan had been dubious. As a youngster with Pack Carno, he had kept pet lizards, but Gork was awfully big to be considered a pet. It was about half Afsan’s own size. Afsan had never seen such a creature before he had been blinded, so he really had only an approximate idea of what Gork looked like. Its hide was dark gray, like slate, according to Cadool, and it constantly tasted the air with a flicking bifurcated tongue. Gork was quite tame, and Afsan had petted it up and down its leathery hide. The reptile’s limbs sprawled out in a push-up posture. Its head was flat and elongated. Its tail was thick and flattened, and it worked from side to side as Gork walked.

Gork gladly wore a leather harness and led Afsan around, always choosing a safe path for its master, avoiding rocks and gutters and dung. Afsan found himself growing inordinately fond of the beast and ascribed to it all sorts of advanced qualities, including at least a rudimentary intelligence.

He was surprised that such pets weren’t more common. It was in some ways pleasant to spend time with another living, breathing creature that didn’t trigger the territorial instinct. Although Gork was cold-blooded, and therefore not very energetic, it was still fast enough as a guide for Afsan, given how slowly Afsan walked most of the time, nervous about tripping.

Afsan and Gork, alone, out among the ancient boulders, wind whipping over them, until…

"Eggling!" A deep and gravelly voice.

Afsan lifted his head up and turned his empty eye sockets toward the sound. It couldn’t be…

"Eggling!" the voice called again, closer now.

Afsan got up off his rock and began to walk toward the approaching visitor. "That’s a voice I haven’t heard in kilodays," he said, surprise and warmth in his tone. "Var-Keenir is that you?"

"Aye."

They approached each other as closely as territoriality would allow. "I cast a shadow in your presence," said Keenir.

Afsan clicked his teeth. "I’ll have to take your word for that. Keenir, it’s grand to hear your voice!"

"And it’s wonderful to see you, good thighbone," said Keenir, his rough tones like pebbles chafing together. "You’re still a scrawny thing, though."

"I don’t anticipate that changing," said Afsan, with another clicking of teeth.

"Aye, it must be in your nature, since I’m sure that at Emperor Dybo’s table there’s always plenty of food."

"That there is. Tell me how you’ve been."

The old mariner’s words were so low they were difficult to make out over the wind, even for Afsan, whose hearing had grown very acute since the loss of his sight. "I’m fine," said Keenir. "Oh, I begin to feel my age, and, except for my regenerated tail, my skin is showing a lot of mottling, but that’s to be expected."

Indeed, thought Afsan, for Keenir had now outlived his creche-mate, Tak-Saleed, by some sixteen kilodays. "What brings you to the Capital?"

"The Dasheter."

Afsan clicked his teeth politely. "Everyone’s a comedian. I mean, what business are you up to?"

"Word went out that a ship was needed for a major voyage. I’ve come to get the job."

"You want to sail to the south pole?"

"Aye, why not? I’ve been close enough to see the ice before, but we never had the equipment for a landing. The Dasheter is still the finest ship

in the world, eggling. It’s had a complete overhaul. And, if you’ll forgive an oldster a spot of immodesty, you won’t find a more experienced captain."

"That much is certain. You know that it is my son Toroca who will be leading the Antarctic expedition?"

"No, I did not know that. But it’s even more fitting. His very first water voyage was aboard the Dasheter, when we brought Novato and your children to Capital City all those kilodays ago. And Toroca took his pilgrimage with me three or four kilodays ago."

"We don’t call it a pilgrimage anymore."

"Aye, but I’m set in my ways. Still, not having to bring along that bombastic priest, Bleen, does make the voyage more pleasant."

Afsan actually thought that Bleen wasn’t a bad sort, as priests went. He said nothing, though.

"Where is Toroca now?" asked Keenir.

"According to his last report, he’s finishing up some studies on the eastern shore of Fra’toolar. He’s expecting a ship to rendezvous with his team there, near the tip of the Cape of Mekt."

"Very good," said Keenir. "Whom do I see about getting this job?"

"The sailing voyage is part of the Geological Survey of Land. That comes under the authority of Wab-Novato, director of the exodus."

"Novato? I’m certain to get the job, then, I daresay."

Afsan clicked his teeth. "No doubt," and then, in a moment of sudden exuberance, he stepped closer to the old mariner. "By the very fangs of God, Keenir, it’s good to be with you again!"

Musings of The Watcher

At last, other intellects! At last, intelligent life native to this iteration of the universe.

It had arisen not on the Crucible, but rather on one of the worlds to which I had transplanted earlier lifeforms. I’d been right: body plans other than those that would have survived the initial weeding of natural selection on the Crucible had the potential for sentience.

They called themselves Jijaki collectively, and each individual was a Jijak.

A Jijak had five phosphorescent eyes, each on a short stalk, arranged in one row of three and a lower row of two. A long flexible trunk depended from the face just below the lower row of eyes. The trunk was made up of hundreds of hard rings held together by tough connective tissue. It ended in a pair of complex cup-shaped manipulators that faced each other. The manipulators could be brought together so that they made one large grasping claw, or they could be spread widely apart, exposing six small appendages within each cup.

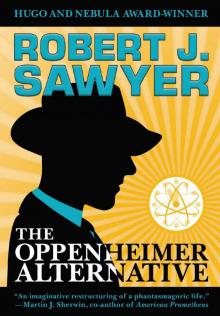

The Oppenheimer Alternative

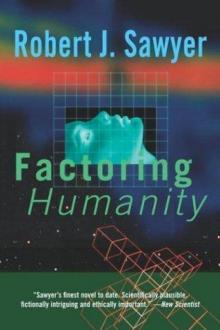

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

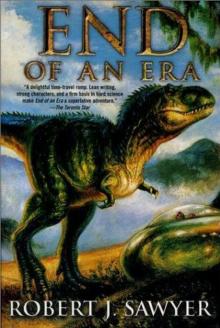

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time