- Home

- Robert J. Sawyer

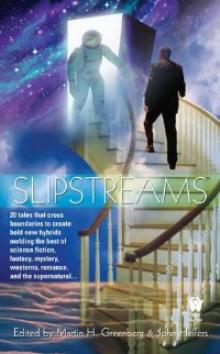

Hominids tnp-1 Page 9

Hominids tnp-1 Read online

Page 9

Chapter 14

The conference room at the Creighton Mine had wall diagrams showing the network of tunnels and drifts. A hunk of nickel ore sat as a centerpiece on a long wooden table. A Canadian flag stood at one end of the room; the other had a large window overlooking the parking lot and the rough countryside beyond.

At the head of the table was Bonnie Jean Mah—a white woman with lots of brown hair who was married to a Chinese-Canadian, hence her last name. She was the director of the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, and had just flown in from Ottawa.

Along one side of the table sat Louise Benoit, the tall, beautiful postdoc who’d been down in the SNO control room when the disaster had occurred. And on the other side sat Scott Naylor, an engineer from the company that had manufactured the acrylic sphere at the heart of SNO. Next to him was Albert Shawwanossoway, Inco’s top expert on rock mechanics.

“All right,” said Bonnie Jean. “Just to bring everyone up to date, they’ve started draining the SNO chamber, before the heavy water gets any more polluted. AECL is going to try to separate the heavy water from the regular water, and, in theory, we should be able to reassemble the sphere and load it up with the recovered heavy water, getting SNO back on-line.” She looked at the faces in the room. “But I’d still like to know exactly what caused the accident.”

Naylor, a balding, tubby white man, said, “I’d say the sphere containing the heavy water burst apart because of pressure from the inside.”

“Could the displacement caused by a man entering the sphere have done that?” asked Bonnie Jean.

Naylor shook his head. “The sphere held 1,100 tonnes of heavy water; you add a human being, weighing a hundred kilos—one-tenth of a tonne—and you’ve only increased the mass by one ten-thousandth. Human beings have about the same density as water, so the displacement increase would only be about one ten-thousandth, as well. The acrylic could easily handle that.”

“Then he must have used an explosive of some sort,” said Shawwanossoway, an Ojibwa of about fifty, with long, black hair.

Naylor shook his head. “We’ve done assays on the water recovered from the tank. There’s no evidence of any explosive—and there aren’t that many that would work soaking wet, anyway.”

“Then what?” asked Bonnie Jean. “Could there have been, I don’t know, a magma incursion or something, and the water boiled?”

Shawwanossoway shook his head. “The temperature of SNO, and the whole mine complex, is closely monitored; there was no change. In the observatory cavern, it held steady at its normal value of 105 degrees—Fahrenheit, that is; forty-one Celsius. Hot, but nowhere near boiling. Remember, too, that the mine is a mile and a quarter underground, meaning the air pressure is about thirteen hundred millibars—30 percent above that at sea level. And at higher pressures, of course, the boiling point goes up, not down.”

“What about the flip side?” asked Bonnie Jean. “What if the heavy water froze?”

“Well, it would indeed have expanded, just like regular water,” said Naylor. He frowned. “Yes, that would have burst the sphere. But heavy water freezes at 3.82 Celsius. It just couldn’t possibly get that cold that far down.”

Louise Benoit joined the conversation. “What if more than just the man entered the sphere? How much material would have to be added before it would burst?”

Naylor thought for a moment. “I’m not sure; it was never specced for that. We always knew exactly how much heavy water AECL was going to loan us.” He paused. “Maybe … I don’t know, maybe 10 percent. A hundred cubic meters, or so.”

“Which is what?” asked Louise. She looked around the conference room. “This room’s about six meters on a side, isn’t it?”

“Twenty feet?” said Naylor. “Yeah, I guess.”

“And it’s got ten-foot ceilings—that’s three meters,” continued Louise. “So you’re talking about a volume of material as big as the contents of this room.”

“More or less, I suppose.”

“That’s ridiculous, Louise,” said Bonnie Jean. “All you found down there was one man.”

Louise nodded, conceding that, but then she lifted her arched eyebrows. “What about air? What if a hundred cubic meters of air were pumped into the sphere?”

Naylor nodded. “I’d thought about that. I thought maybe a belch of gas had somehow welled up into the sphere, although how it would get inside I have no idea. The water samples we took were somewhat aerated, but …”

“But what?” asked Louise,

“Well, they were indeed aerated, with nitrogen, oxygen, and some CO2, as well as some gabbroic rock dust and pollen. In other words, just regular mine air.”

“Then it couldn’t have come from the SNO facility,” said Bonnie Jean.

“That’s right, ma’am,” said Naylor. “That air is all filtered; it’s free of rock dust and other pollutants.”

“But the only parts of the mine connecting to the detector chamber are in the SNO facility,” said Louise.

Naylor and Shawwanossoway both nodded.

“Okay, okay,” said Bonnie Jean, steepling her fingers in front of her. “What have we got? The volume of material inside the sphere was increased by, at a guess, 10 percent or more. That might have been caused by an infusion of a hundred cubic meters or more of unfiltered air—although unless the air was pumped in very rapidly, it would have been compressed by the weight of the water, no? And, in any event, we don’t know where the air came from—it certainly wasn’t from SNO—or how it was conveyed into the sphere, right?”

“That’s about the size of it, ma’am,” said Shawwanossoway.

“And this man—we don’t know how he got into the sphere, either?” asked Bonnie Jean.

“No,” said Louise. “The access hatch between the inner heavy-water sphere and the outer regular-water containment tank was sealed tight even after the sphere broke apart.”

“All right,” said Bonnie Jean, “do we know how this—this Neanderthal, they’re calling him—even got down into the mine?”

Shawwanossoway was the only one present who actually worked for Inco. He spread his arms. “The mine-security people have reviewed the security-camera tapes and access logs for the forty-eight hours prior to the incident,” he said. “Caprini—that’s our head of security—swears that heads will roll when he finds out who screwed up by letting that guy in, and he says even worse will happen when he finds out who’s been trying to hide it.”

“What if no one is lying?” said Louise.

“That’s just not possible, Miss Benoit,” said Shawwanossoway. “No one could get down to SNO without it being recorded.”

“No one could if he came down by the elevator,” said Louise. “But what if he didn’t come that way?”

“You think maybe he climbed down two kilometers of vertical air shafts?” said Shawwanossoway, scowling. “Even if he could do that—and it would take nerves of steel-security cameras still would have recorded him.”

“That’s my point,” said Louise. “He obviously didn’t go down into the mine. As Professor Mah said, they’re calling him a Neanderthal—but he’s a Neanderthal with some sort of high-tech implant on his wrist; I saw that with my own eyes.”

“So?” said Bonnie Jean.

“Please!” exclaimed Louise. “You all must be thinking the same things I’m thinking. He didn’t take the elevator. He didn’t go down the ventilation shafts. He materialized inside the sphere—him, and a roomful of air.”

Naylor whistled the opening notes of the original Star Trek theme.

Everyone laughed.

“Come on,” said Bonnie Jean. “Yes, this is a crazy situation, and it might be tempting to jump to crazy conclusions, but let’s stay down to earth.”

Shawwanossoway could whistle, too. He did the theme to The Twilight Zone.

“Stop that!” snapped Bonnie Jean.

Chapter 15

Mary Vaughan was the only passenger on the Inco Learjet flying from Toronto to Sudbury;

she’d noted on boarding that the plane, painted with dark green sides, was labeled “The Nickel Pickle” on its bow.

Mary used the brief flight time to review research notes on her notebook computer; it had been years since she’d published her study of Neanderthal DNA in Science. As she read through her notes, she twirled the gold chain that held the small, plain cross she always wore around her neck.

In 1994, Mary had made a name for herself recovering genetic material from a 30,000-year-old bear found frozen in Yukon permafrost. And so, two years later, when the Rheinisches Amt fur Bodendenkmalpflege—the agency responsible for archeology in the Rhineland—decided it was time to see whether any DNA could be extracted from the most famous fossil of all, the original Neanderthal man, they called on Mary. She’d been dubious: that specimen was desiccated, having never been frozen, and—opinions varied—it might be as old as 100,000 years, three times the age of the bear. Still, the challenge was irresistible. In June 1996, she’d flown to Bonn, then headed to the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, where the specimen was housed.

The best-known part—the browridged skullcap—was on public display, but the rest of the bones were kept in a steel box, within a steel cabinet, inside a room-sized steel vault. Mary was led into the safe by a German bone preparator named Hans. They wore protective plastic suits and surgeons’ masks; every precaution had to be taken against contaminating the bones with their own modern DNA. Yes, the original discoverers had doubtless contaminated the bones—but after a century and a half, their unprotected DNA on the surface should have degraded completely.

Mary could only take a very small piece of bone; the priests at Turin guarded their shroud with equal jealousy. Still, it was extraordinarily difficult for both her and Hans—like desecrating a great work of art. Mary found herself wiping away tears as Hans used a goldsmith’s saw to cut a semicircular chunk, just a centimeter wide and weighing only three grams, from the right humerus, the best preserved of all the bones.

Fortunately, the hard calcium carbonate in the outer layers of the bone should have afforded some protection for any of the original DNA within. Mary took the specimen back to her lab in Toronto and drilled tiny pieces out of it.

It took five months of painstaking work to extract a 379-nucleotide snippet from the control region of the Neanderthal’s mitochondrial DNA. Mary used the polymerase chain reaction to reproduce millions of copies of the recovered DNA, and she carefully sequenced it. She then checked the corresponding bit of mitochondrial DNA in 1,600 modern humans: Native Canadians, Polynesians, Australians, Africans, Asians, and Europeans. Every one of those 1,600 people had at least 371 nucleotides out of those 379 the same; the maximum deviation was just eight nucleotides.

But the Neanderthal DNA had an average of only 352 nucleotides in common with the modern specimens; it deviated by a whopping twenty-seven bases. Mary concluded that her kind of human and Neanderthals must have diverged from each other between 550,000 and 690,000 years ago for their DNA to be so different. In contrast, all modern humans probably shared a common ancestor 150,000 or 200,000 years in the past. Although the half-million-year-plus date for the Neanderthal/modern divergence was much more recent than the split between genus Homo and its closest relatives, the chimps and bonobos, which occurred five to eight million years ago, it was still far enough back that Mary felt Neanderthals were probably a fully separate species from modern humans, not just a subspecies: Homo neanderthalensis, not Homo sapiens neanderthalensis.

Others disagreed. Milford Wolpoff of the University of Michigan was sure that Neanderthal genes had been fully co-opted into modern Europeans; he felt any test strand that showed something different was, therefore, an aberrant sequence or a misinterpretation.

But many paleoanthropologists agreed with Mary’s analysis, although everyone—Mary included—said that further studies needed to be done to be sure … if only more Neanderthal DNA could be found.

And now, maybe, just maybe, more had been found. There was no way this Neanderthal man could be real, thought Mary, but if it were …

Mary closed her laptop and looked out the window. Northern Ontario spread out below her, with Canadian Shield rocks exposed in many places and aspen and birch dotting the landscape. The plane was beginning its descent.

* * *

Reuben Montego had no idea what Mary Vaughan looked like, but since there were no other passengers aboard the Inco jet, he didn’t have any trouble spotting her. She turned out to be white, in her late thirties, with honey-blond hair showing darker roots. She was perhaps ten pounds overweight, and, as she came closer, Reuben could see that she clearly hadn’t gotten much sleep the night before.

“Professor Vaughan,” Reuben said, offering his hand. “I’m Reuben Montego, the M.D. at the Creighton Mine. Thank you so very much for coming up.” He indicated the young woman he’d picked up on the way to the Sudbury airport. “This is Gillian Ricci, the press officer for Inco; she’s going to look after you.”

Reuben thought Mary looked inordinately pleased to see the attractive young woman who was accompanying him; maybe the professor was a lesbian. He reached out to take the suitcase Mary was holding. “Here, let me help you.”

Mary relinquished the bag, but she fell in beside Gillian, rather than Reuben, as they walked across the tarmac, the summer sun beating down. Reuben and Gillian were both wearing sunglasses; Mary was squinting against the brightness, evidently having forgotten to bring a pair.

When they arrived at Reuben’s wine-colored Ford Explorer, Gillian politely began to get in the backseat, but Mary spoke up. “No, I’ll sit there,” she said. “I—ah—I want to stretch out.”

Her odd statement hung between them for a second, and then Reuben saw Gillian shrug a little and move up to the front passenger’s seat.

They drove directly to St. Joseph’s Health Centre, on Paris Street, just past the snowflake-shaped museum Science North. Along the way, Reuben briefed Mary about the accident at SNO and the strange man who had been found.

As they pulled into the hospital parking lot, Reuben saw three vans from local TV stations. Surely hospital security was keeping reporters away from Ponter, but, just as surely, the journalists would be following this story closely.

When they arrived at Room 3-G, Ponter was standing up, looking out the window, his broad back to them. He was waving—and Reuben realized that TV cameras must be trained up at his window. A cooperative celebrity, thought Reuben. The media are going to love this guy.

Reuben coughed politely, and Ponter turned around. He was backlit by the window and still hard to make out. But as he stepped forward, the doctor enjoyed watching Mary’s jaw drop when she got her first good look at the Neanderthal. She’d briefly seen Ponter on TV, she’d said, but that seemingly hadn’t prepared her for the reality.

“So much for Carleton Coon,” Mary said, after apparently recovering her wits.

“Say what?” said Reuben sharply.

Mary looked puzzled, then flustered. “Oh, my, no. Carleton Coon. He was an American anthropologist. He’s the guy who said if you dressed a Neanderthal up in a Brooks Brothers suit, he’d have no trouble passing for a regular human.”

Reuben nodded. “Ah,” he said. Then: “Professor Mary Vaughan, I’d like you to meet Ponter.”

“Hello,” said the female voice from Ponter’s implant.

Reuben saw Mary’s eyes go wide. “Yes,” he said, nodding. “That thing on his wrist is talking.”

“What is it?” asked Mary. “A talking watch?”

“Much more.”

Mary leaned in for a look. “I don’t recognize those numerals, if that’s what they are,” she said. “And—say—aren’t they changing too fast for seconds?”

“You’ve got a good eye,” said Reuben. “Yeah, they are. The display uses ten distinct numerals, although none of them look like any I’ve ever seen. And I timed it: it increments every 0.86 seconds, which, if you work it out, is exactly one one-hundred-thousandth of a day. In othe

r words, it’s a decimal-counting Earth-based time display. And, as you can see, it’s a very sophisticated device. That’s not an LCD; I don’t know what it is, but it’s readable no matter what angle you look at it or how much light is falling on it.”

“My name is Hak,” said the implant on the strange man’s left wrist. “I am Ponter’s Companion.”

“Ah,” said Mary, straightening up. “Um, glad to know you.”

Ponter made a series of deep sounds that Mary couldn’t understand. Hak said, “Ponter is glad to know you, too.”

“We spent the morning having a language lesson,” said Reuben, looking now at Mary. “As you can see, we’ve made some real progress.”

“Apparently,” said Mary, astonished.

“Hak, Ponter,” said Reuben. “This is Gillian.”

“Hello,” said Hak. Ponter nodded in agreement.

“Hello,” said Gillian, trying, Reuben thought, to remain composed.

“Hak is—well, I guess ‘computer’ is the right term. A talking, portable computer.” Reuben smiled. “Beats all hell out of my Palm Pilot.”

“Does—does anyone make a device like that?” asked Gillian.

“Not as far as I know,” said Reuben. “But she—Hak—has an apparently perfect memory. Tell her a word once, and she’s got it for good.”

“And this man, this Ponter, he really doesn’t speak English?” asked Mary.

“No,” said Reuben.

“Incredible,” said Mary. “Incredible.”

Ponter’s implant bleeped.

“Incredible,” repeated Reuben, turning to Ponter. “It means not believable”—another bleep—“not true.” He faced Mary again. “We worked out the concepts of true and false using some simple math, but, as you can see, we’ve still got a ways to go. For one thing, although it clearly seems easier for Hak, with her perfect memory, to learn English, than for us to learn her language, neither she nor Ponter can make the ee sound, and—”

The Oppenheimer Alternative

The Oppenheimer Alternative Factoring Humanity

Factoring Humanity The Shoulders of Giants

The Shoulders of Giants Stream of Consciousness

Stream of Consciousness End of an Era

End of an Era The Terminal Experiment

The Terminal Experiment Far-Seer

Far-Seer Mindscan

Mindscan You See But You Do Not Observe

You See But You Do Not Observe Star Light, Star Bright

Star Light, Star Bright Wonder

Wonder Wiping Out

Wiping Out Flashforward

Flashforward Above It All

Above It All Frameshift

Frameshift The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids

The Neanderthal Parallax, Book One - Hominids Foreigner

Foreigner Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids

Neanderthal Parallax 1 - Hominids Relativity

Relativity Identity Theft

Identity Theft Hybrids np-3

Hybrids np-3 Foreigner qa-3

Foreigner qa-3 WWW: Watch

WWW: Watch Calculating God

Calculating God The Terminal Experiment (v5)

The Terminal Experiment (v5) Peking Man

Peking Man The Hand You're Dealt

The Hand You're Dealt Illegal Alien

Illegal Alien Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids

Neanderthal Parallax 3 - Hybrids Fossil Hunter

Fossil Hunter WWW: Wonder

WWW: Wonder Iterations

Iterations Red Planet Blues

Red Planet Blues Rollback

Rollback Watch w-2

Watch w-2 Gator

Gator Triggers

Triggers Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans

Neanderthal Parallax 2 - Humans Wonder w-3

Wonder w-3 Wake

Wake Just Like Old Times

Just Like Old Times Wake w-1

Wake w-1 Fallen Angel

Fallen Angel Hybrids

Hybrids Hominids tnp-1

Hominids tnp-1 Far-Seer qa-1

Far-Seer qa-1 Starplex

Starplex Hominids

Hominids Identity Theft and Other Stories

Identity Theft and Other Stories Watch

Watch Golden Fleece

Golden Fleece Quantum Night

Quantum Night Fossil Hunter qa-2

Fossil Hunter qa-2 Humans np-2

Humans np-2 Biding Time

Biding Time